Seeing Each Other: Portraits of Artists, Pallant House Gallery

Six works from the Katrin Bellinger Collection are currently on view at Pallant House Gallery (in Chichester) in the exhibition Seeing Each Other: Portraits of Artists (17 May–2 November 2025). Featuring twentieth- and twenty-first-century British art, the exhibition explores how artists engage with one another—as friends, rivals, and sources of inspiration. Since the topic is so clearly in dialogue with the Artists at Work theme, the Katrin Bellinger Collection happily loaned three prints, two photographs, and a charcoal and watercolor drawing to the exhibition.

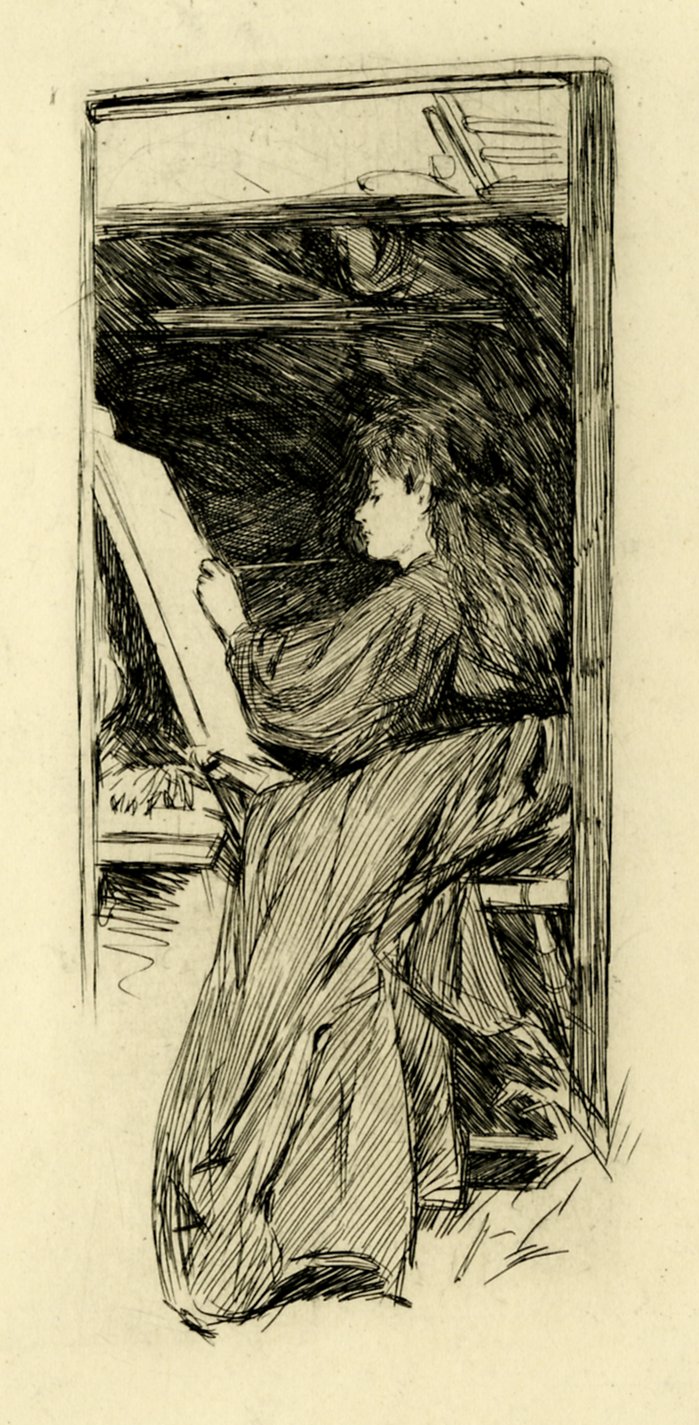

The earliest drawing in this selection is by Thérèse Lessore, the British modernist artist who was a founding member of the London Group (Fig. 1). In her charcoal and watercolor drawing from 1919, Lessore depicts the painter Walter Sickert in front of a window. The artists were close friends and had frequented the same British modernist circles since c. 1910; they would go on to marry in 1926. Bill Brandt’s photograph Ben Nicholson at His Studio in St. Ives shows the abstract painter from behind, focusing on his hands as he draws. Nicola Bensley also zooms in on Frank Auerbach’s hand in her photograph, emphasizing the artist’s creative power (Fig. 2). All of these works present exchanges between artists that feel like intimate conversations.

The exhibition also embraces imagined relationships, where artistic influence crosses generations and national affiliations: for example, two of the prints that the Katrin Bellinger Collection loaned to the show rethink Velázquez’s Las Meninas (Prado inv. P001174). Michael Craig-Martin transposes the iconic Velázquez painting into an explosion of color, while Richard Hamilton’s Picasso’s Meninas looks at Velázquez via Picasso, who also reinterpreted the scene in the 1950s (Figs. 3). David Hockney also cites Picasso as an important influence in The Student: Homage to Picasso.

These works—and the many others in the show—make evident the intricate networks of influence that profoundly shape the lives and careers of artists.

Seeing Each Other: Portraits of Artists is on view at Pallant House Gallery from 17 May – 2 November 2025.

Figure 1: Thérèse Lessore, Walter Sickert Drawing in Front of a Mirror, 1919. Charcoal and watercolor, 25.7 x 20.7 cm. Katrin Bellinger Collection inv. 2021-085.

Figure 2: Nicola Bensley, Hand of Frank Auerbach, 2015. Silver gelatine fibre based hand print, 50.8 x 40.6 cm. Katrin Bellinger Collection inv. 2016-021.

Figure 3: Richard Hamilton, Picasso’s Meninas, 1973. Etching, aquatint, engraving, and drypoint. 75.5 x 56.7 cm (sheet); 57.1 x 49.1 cm (image). Katrin Bellinger Collection inv. 2015-003.

The Gorgeous Nothings: Flowers at Chatsworth

The Gorgeous Nothings: Flowers at Chatsworth (15 March – 5 October 2025) is a transhistorical exhibition that the organizers have described as a “gathering,” a careful act of bringing together objects that engage with flowers and plant life. Drawing inspiration from the Chatsworth estate, and displayed throughout the house and its gardens, the exhibition is comprised of works from the Devonshire Collections, external loans, and commissions by contemporary artists. From sculpture to painting, fashion to engravings, the exhibition celebrates botany as an inspirational force for artists, designers, gardeners, scientists and creators of all kinds.

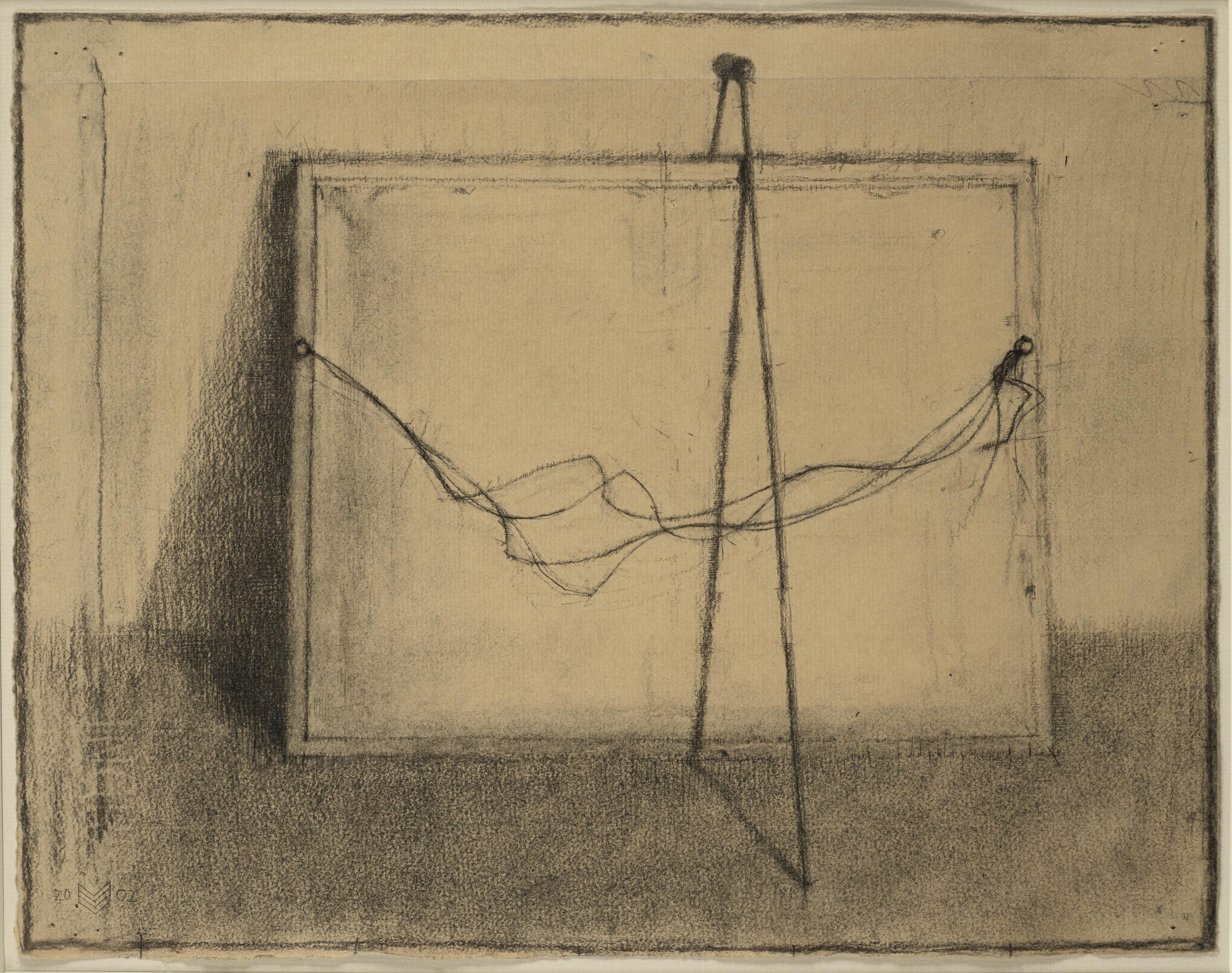

The Katrin Bellinger Collection has loaned the 2021 drawing Personal Development (fig. 1) by Donna Huddleston, which is beautifully presented on an easel in the house (fig. 2). Huddleston’s ethereal caran d’ache and graphite drawing depicts a figure in front of Venetian blinds; a compositional frame separates the figure from a large pink flower. Although the work is not a straightforward self-portrait, the woman stands for the artist herself in a theatrical and performative way. The delicate color palette of yellow-greens, pinks, and blues is suggestive of botanical watercolors, and the textured flatness of the flower evokes pressed flowers—which are also displayed in the Chatsworth exhibition.

The Gorgeous Nothings: Flowers at Chatsworth is curated by Allegra Pesenti and designed by Pippa Nissen (Nissen Richards Studio).

Figure 1: Donna Huddleston (Belfast 1970–), Personal Development, 2021. Caran d’ache and graphite on paper, 66 x 51 cm. Katrin Bellinger Collection inv. 2022-001.

Figure 2: Installation view

Barbara Walker: Being Here, The Whitworth and Arnolfini

The Katrin Bellinger Collection recently loaned Barbara Walker’s Marking the Moment I (fig. 1) to the artist’s first major survey exhibition, Barbara Walker: Being Here, which travelled from the Whitworth, University of Manchester to Arnolfini in Bristol. Being Here traced Walker’s figurative work from the 1990s to today through a presentation of almost 60 works. It conveyed Walker’s dedication to tackling contemporary issues of race, class, and gender head-on, which she accomplishes through powerful portraits of her family and her community, as well as reinterpretations of historic images.

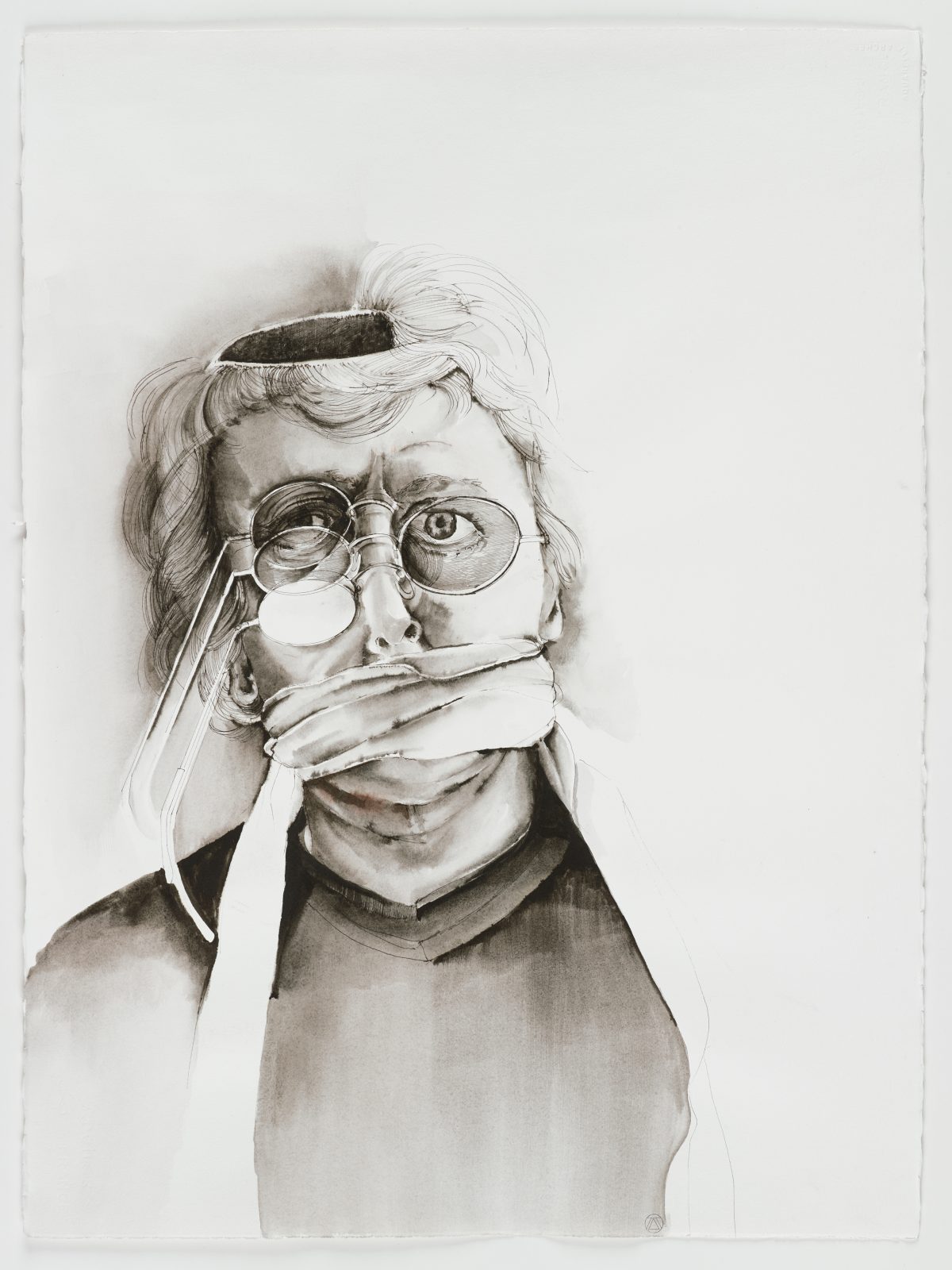

Marking the Moment I is part of a larger series of drawings produced between 2021 and 2024. To produce each drawing, Walker began by recreating a print from either the British Museum or the Rijksmuseum’s collections. She then placed translucent mylar over the work and strategically cut it to render the Black figures visible. In so doing, Walker reverses the compositional hierarchies that structure many of these prints, where Black figures are positioned in the margins.

Another drawing by Walker has recently joined the collection: Self-Portrait V (Venice) (fig. 2). Also part of a series, this large conté and charcoal drawing deliberately plays with the dialogue between finished and unfinished. Walker produced it during a 2025 residency in Venice, where she reflected on the experience of being anonymous in a new city and was particularly inspired by the sixteenth-century artist Jacopo Tintoretto’s compositions that look down from a high angle.

Barbara Walker: Being Here was first presented at the Whitworth, University of Manchester from 4 October 2024 – 26 January 2025, and was on view at Arnolfini from 8 March – 25 May 2025. The exhibition is also accompanied by a catalogue.

Figure 1: Barbara Walker, Marking the Moment I, 2021. Graphite on paper overlaid with mylar, 334 x 419 mm. Misc. 16284.

Figure 3: Barbara Walker, Self Portrait V (Venice), 2025. Conté and charcoal on paper, 100.3 x 70.1 cm. Katrin Bellinger Collection inv. 2025-030.

Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800

Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800 set out to celebrate the “polyphonic contributions of women makers,” and this emphasis on multiplicity—of voices, of origins, and of media—elevates entire categories of making that are only now receiving their due.[1] From embroidery to cut paper, drawing to print, the exhibition and its catalogue place materiality and medium front and center. Curated by Andaleeb Badiee Banta and Alexa Greist, with the assistance of Theresa Kutasz Christensen, the exhibition is no longer open, but it was on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art (1 Oct 2023–7 Jan 2024) and the Art Gallery of Ontario (30 March–1 July 2024). I would enthusiastically recommend the catalogue essays to anyone who, like me, missed the opportunity to see the show in person!

We may now recognize “greatness” as a problematic category for art history,[2] but here the curators also unpack how similar terms like “exceptionality” and “quality” preclude us from considering the creative outputs of most historical women.[3] Our emphases on attributions, on “fine art” (read: painting), and single-person authorship necessarily excludes most work by women, who are often anonymous, have created collaboratively, or worked under the auspices of “craft.” This underpins the curators’ decision to consider a wide geographic and temporal range, through which they can more accurately capture the diverse experiences of women living under varying socio-political conditions.[4] Labor of all kinds shines through the 230-plus objects exhibited.

A Spotlight on Revolutionary France

Some patterns, however, emerge from the polyphony. The Katrin Bellinger Collection loaned five works to the exhibition—three drawings, one album, and a combination sewing and watercolor kit. Two of these drawings speak to a particular historical moment in late eighteenth-century Paris, when the reorganization of art institutions before, during, and after the Revolution created new pathways for women to access training and exhibition spaces.

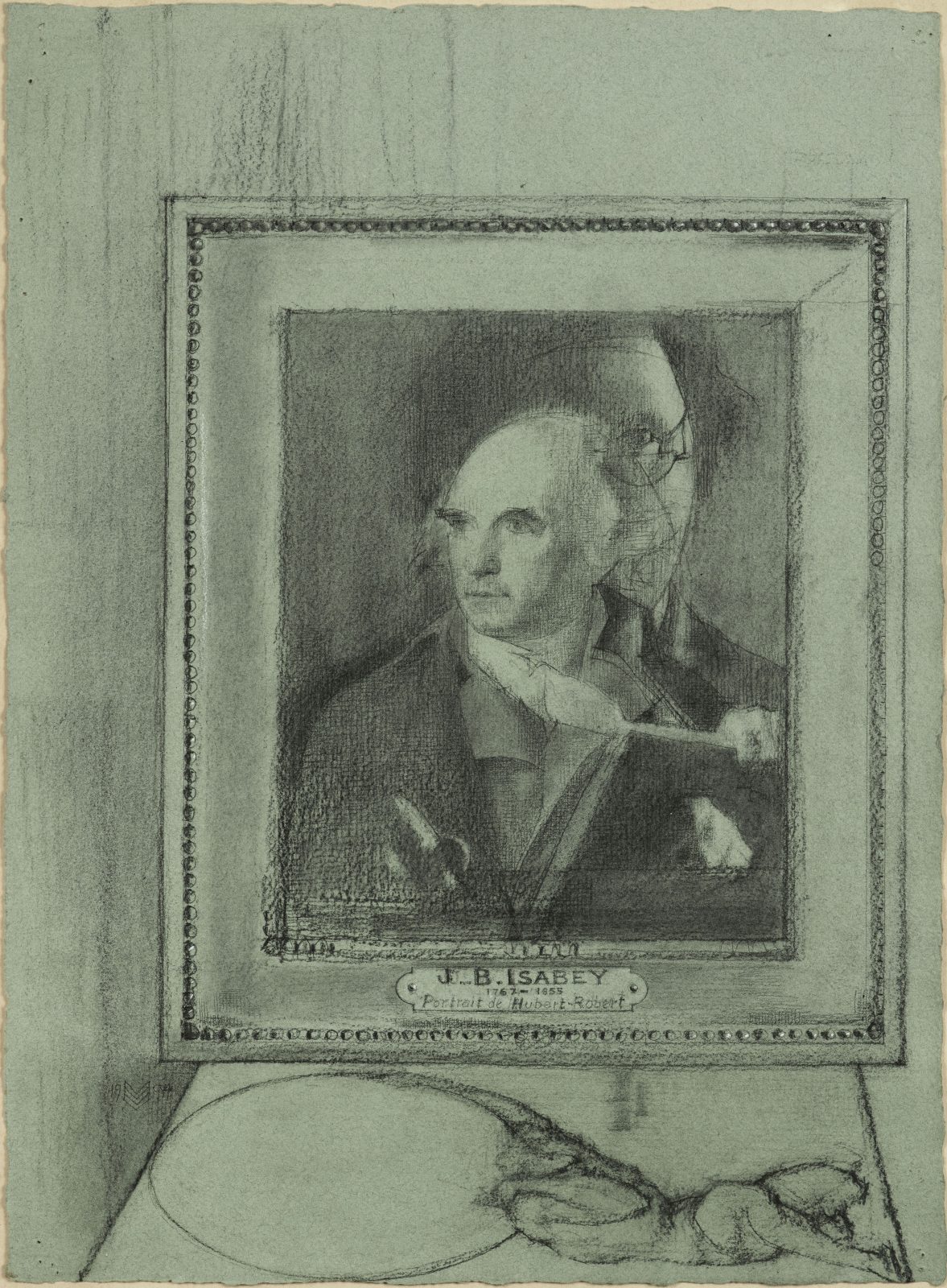

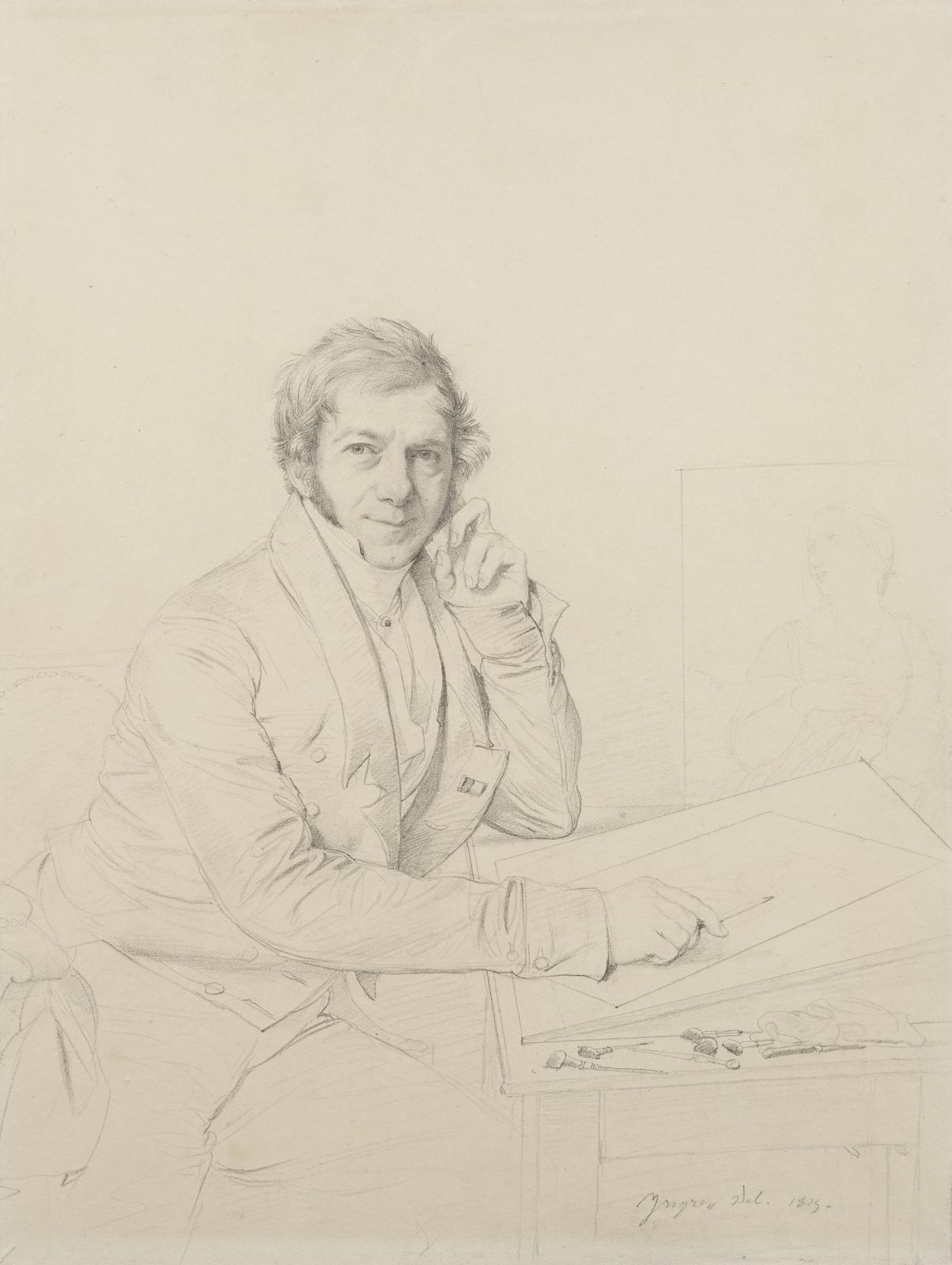

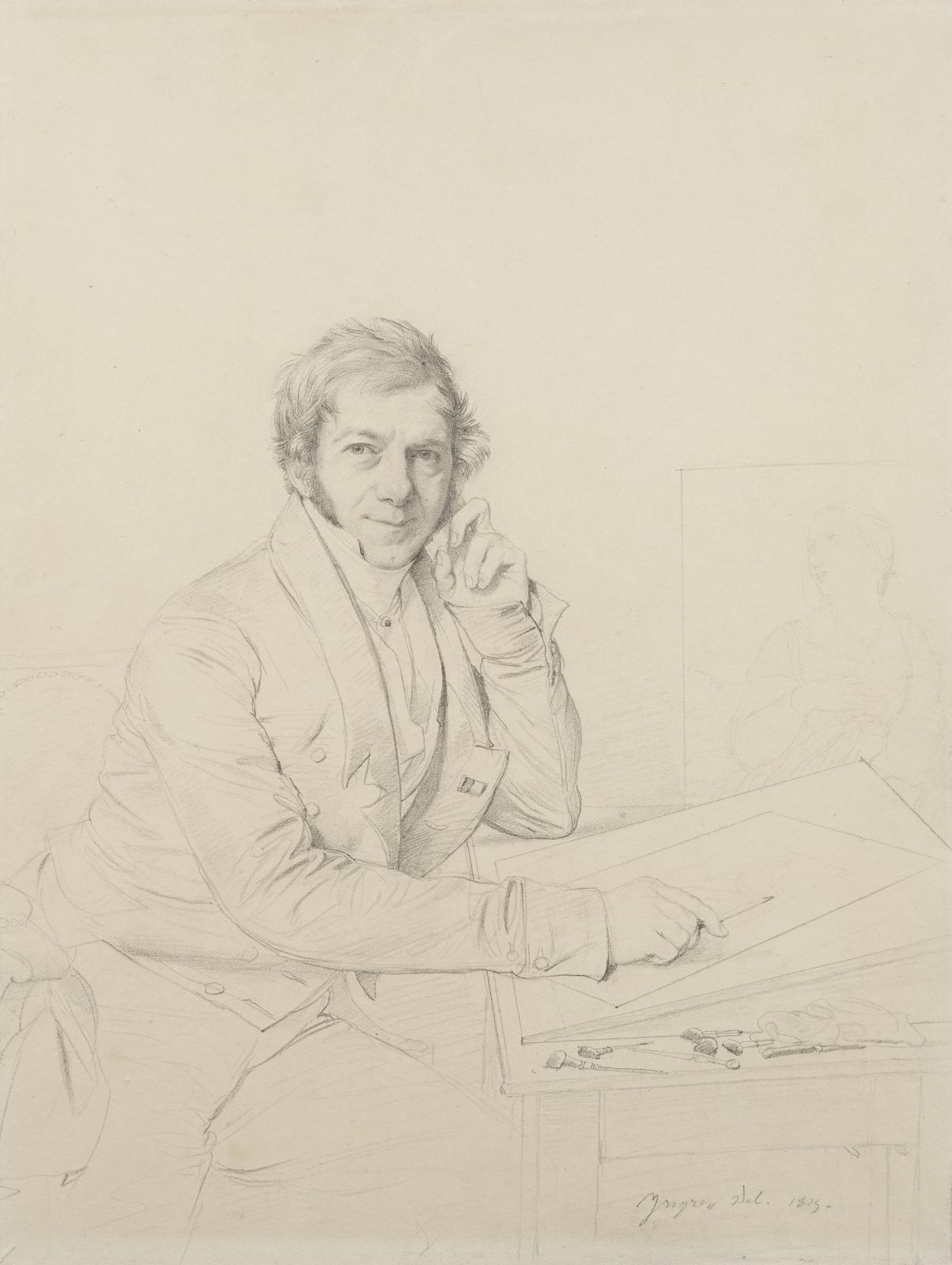

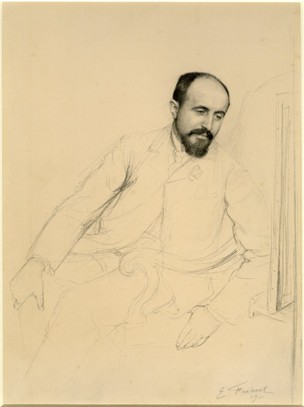

Marie-Gabrielle Capet’s (1761–1818) sensitive chalk portrait of the aging painter François-André Vincent (1746–1816) divulges her close friendships with both men and women artists (Fig. 1). Vincent, a prominent neoclassical artist, was married to Capet’s teacher and mentor, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803), and the three functioned much like a family. The latter was one of only a handful of women admitted to the Académie, and when she received artist’s lodgings in the Louvre in 1795, Capet joined her.[5] This miniature-like portrait attests to a continued closeness between Vincent and Capet after Labille-Guiard’s death. Capet looked after Vincent in his final years, and in her will she described the work as an image of “her father.”[6]

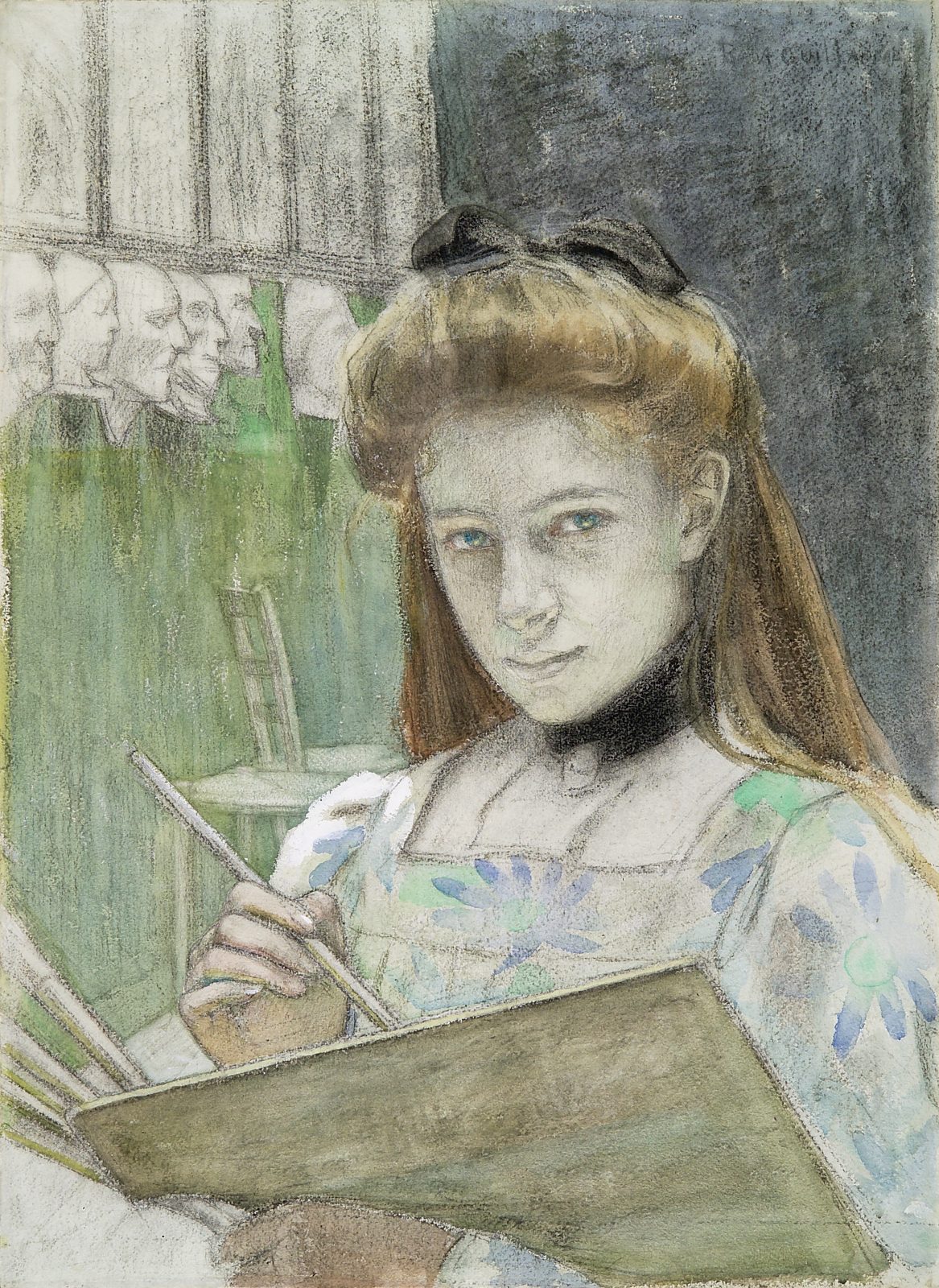

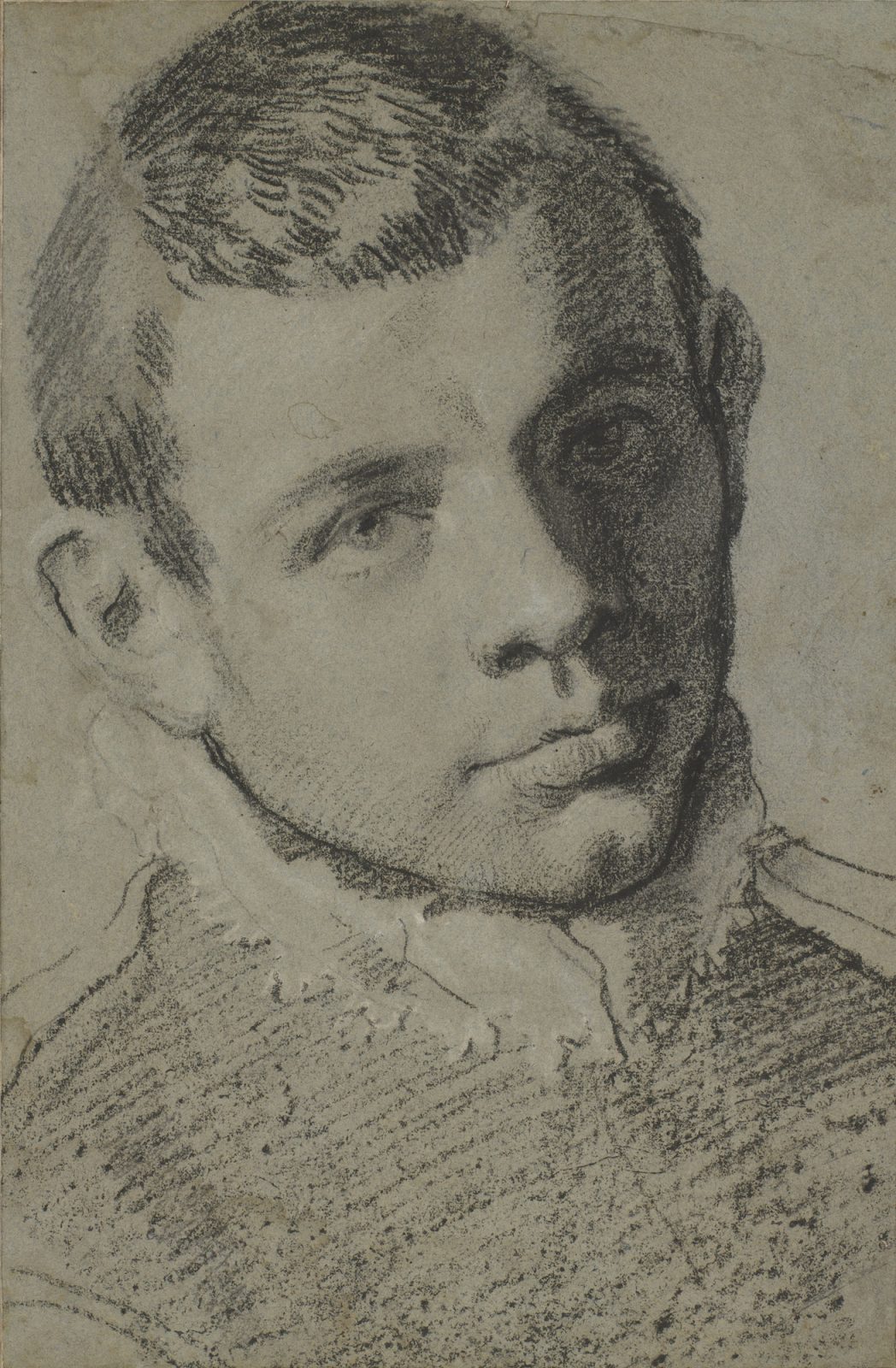

Anne Guéret (1760–1805), Capet’s almost exact contemporary, was a student of neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David, and her attractive portrait of a fellow artist features on the cover of the exhibition catalogue (Fig. 2). Guéret’s sitter is captured in a moment of inspiration: gazing up and to the left of the sheet, a soft halo of light encircles her head. She appears relaxed and in control of her work, with her arm draped casually over her portfolio. Her unfinished sketch is, notably, a winged male nude, which alludes to one of the central challenges for women artists in the academy: the so-called “impropriety” of studying the male body from life. Guéret thus stakes a claim to the capabilities of women artists to depict the male nude, both for her sitter, and by association for herself.[7]

The Amateur and the Professional

Both Gueret and Capet produced art for the public sphere, garnering them the status of “professional” artists. Conversely, the nineteenth-century Combination Sewing and Painting Box shines a light on “amateur” makers who often worked in multiple media within the private spaces of the home (Fig. 3). Fanny Guillaume Baronne de Molaret’s 1837 album of drawings contains sketches that attest to such domestic social settings where women made art without plans to exhibit or sell (Figs. 4, 5). Again, though, the curators have made clear that amateur and professional are value judgements that have historically diminished the seriousness of art made by women.

Such arbitrary distinctions between “amateur” and “professional” are intimated in Louise Adéone Drölling’s (1797–1831) oil painting Interior with Young Woman Tracing a Flower (Fig. 6).[8] In this work, a possible self-portrait, the artist is portrayed alongside a lute and other objects that indicate her participation in acceptable creative pursuits for upper-class women. However, Drölling herself was trained by her father and won a gold medal for the painting when it was exhibited in 1824. Furthermore, the composition was disseminated in printed form: a publicly commercial enterprise (Fig. 7).

The full scope of the show is best appreciated by parsing the rich catalogue, or by exploring the digital resources on the Art Gallery of Ontario’s website. Making Her Mark introduces us to a new array of artists and objects, while offering insightful methods for studying them further.

Link to exhibition catalogue:

Notes:

[1] Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Alexa Greist, and Theresa Kutasz Christensen, eds., Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800 (Toronto, Ontario: Art Gallery of Ontario in association with Goose Lane Editions, 2023), 9.

[2] See Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” in Art and Sexual Politics, eds. Elizabeth C. Baker and Thomas B. Hess (London: Collier Macmillan, 1973); Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology (London: Pandorra, 1981).

[3] Andaleeb Badiee Banta, “Not Seen, Not Heard: In Search of the Unexceptional Woman Artist,” in Banta, Greist, and Kutasz Christensen, Making Her Mark, 15–28.

[4] Banta, Greist, and Kutasz Christensen, Making Her Mark, 18.

[5] See note 2, Séverine Sofio, “Gabrielle Capet’s Collective Self-Portrait: Women and Artistic Legacy in Post-Revolutionary France,” Journal18, no. 8, Self/Portrait (Fall 2019), https://www.journal18.org/4397

[6] See catalogue essay, Coutau-Bégarie & Associés, 10 February 2021, lot 25, 47.

[7] The work has also been interpreted as a self-portrait due to resemblances between the subject and a later portrait of Anne Guéret. See catalogue essay, Stephen Ongpin Fine Art, An Exhibition of Master Drawings, New York & London 2008, no. 22.

[8] Banta, Greist, and Kutasz Christensen, Making Her Mark, 216.

Fig. 1: Marie-Gabrielle Capet, Portrait of the Painter François-André Vincent, 1811, black chalk, red chalk, and white chalk on paper. Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2021-024.

Fig. 2: Anne Guéret, Portrait of an Artist with a Portfolio (Self-Portrait?), c. 1793, black chalk, pen and grey ink, and wash, heightened with white gouache on paper. Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2008-012.

Fig. 3: English, probably Reeves & Company, A George III Combination Sewing and Painting Box, 19th century. Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2017-005.

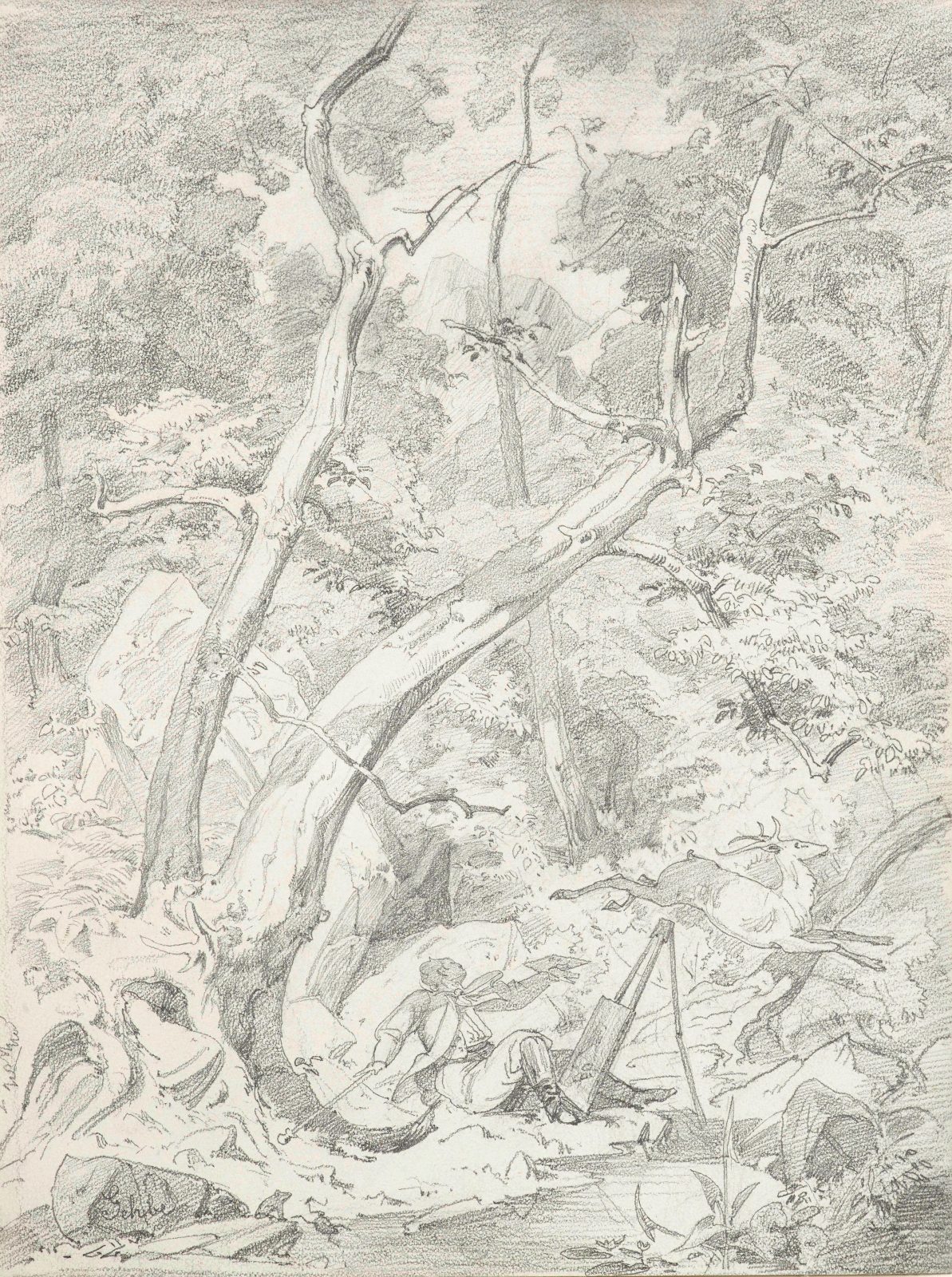

Fig. 4: Fanny Guillaume Baronne de Molaret, Landscape Painter at Her Easel, 1837, graphite on vellum paper, from a drawing album. Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2015-017.

Fig. 5: Fanny Guillaume Baronne de Molaret, Woman Mending a Bodice, 1837, graphite on vellum paper, in a drawing album. Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2015-017.

Fig. 6: Louise Adéone Drölling, Interior with Young Woman Tracing a Flower, c. 1820–1822, oil on canvas. Saint Louis Art Museum.

Fig. 7: Fréderic Weber after Louise Adéone Drölling, A Young Woman Tracing a Flower, n.d., lithograph. Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2021-053.

Countless Discoveries and Rediscoveries: British Women Artists at Tate Britain

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520–1920 exceeds the promise of its title: it brings out of the shadows (and storerooms!) works by more than one hundred women artists who have been historically hidden from public view. Curated by Tabitha Barber and Tim Batchelor, the exhibition, open at Tate Britain until 13 October 2024, integrates works from the Tate’s holdings with loans from public and private collections. It is an undeniably impressive show, ambitious in its aim to trace a history of British art exclusively by women. Along with other recent exhibitions such as Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800, and Women Masters, Now You See Us is an important reminder that many women artists still remain on the margins of our understanding of art history.

The exhibition unfolds in a loose chronology, ranging from Tudor-era miniatures to Modern British painting. Within this broad chronological framework, the show and catalogue are organized around thematic clusters that prompt an exploration of certain subject matter or media that women particularly excelled at, such as flower painting or watercolour. Institutional obstacles are also dealt with thematically, with sections like The First Professionals and Art School.[1] Better-known works by artists such Angelica Kauffman, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Vanessa Bell are interspersed with less familiar but equally compelling works, such as Mary Beale’s Self-portrait as Artemisia (c. 1675; Fig. 1), Louise Jopling’s Through the Looking-Glass (1875; Fig. 2) recently acquired by Tate Britain, or the intricate The Deceitfulness of Riches (1901) by Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, a Neo-Pre-Raphaelite.

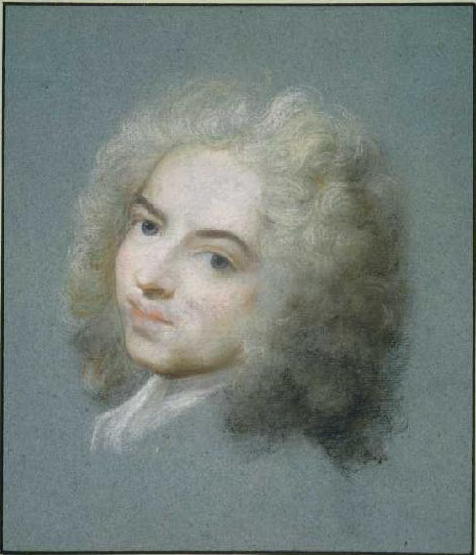

Miss Helena Beatson, a pastel by Katherine Read (1723–1778), is on loan to the exhibition from the Katrin Bellinger Collection (Fig. 3). Seven additional portraits by Read appear in the show—three in pastel and four in oil—which comprises a substantial portion of the eighteenth-century works presented. Read was born in Scotland in 1723 and trained in Paris and Rome with Maurice-Quentin de La Tour before establishing her London studio.[2] Unlike many of the artists that Now You See Us introduces, Read did not come from an artistic family. She found an initial clientele for her portraits through her family’s Jacobite contacts, which she subsequently built upon as her reputation grew. She exhibited at many of the most coveted venues, including the Royal Academy, the Free Society, and the Society of Artists, and was commercially successful.

Read may have been inspired to work in pastel as well as oil because of her training with La Tour, who was a celebrated pastelist. However, pastel was also a more accepted medium for women artists: it was associated with contemporary stereotypes of femininity because of its softness and delicacy. Like watercolor and needlework, pastel was considered a less “serious” medium than oil, despite its immense popularity among eighteenth-century collectors. This meant that women artists working in these media could more easily avoid vehement criticism while achieving commercial success. Read’s technical handling in Miss Helena Beatson is exquisite; she creates soft and blended passages in her subject’s hair, skin, and fabric, while retaining a detailed sharpness in the necklace, pen and drawing.

The portrait also exacerbates an unanticipated—and joyful—theme that emerges from the exhibition. In the face of countless challenges, both institutional and social, women artists regularly forged support networks with each other and with their patrons. For example, Read met the renowned Italian artist Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757) on a visit to Venice in 1753, and the two discussed pastel techniques.[3] Miss Helena Beatsonis a depiction of Read’s orphaned niece: five years old at the time of sitting, Beatson was considered a child prodigy.[4] The portrait shows the young sitter in the act of drawing a mother and child; it may be an art lesson, as Read taught Beatson. Unlike Read, Beatson chose not to pursue art as a profession, and halted her practice when she reached adulthood. Nevertheless, Read left much of her money to her female nieces in the hopes of providing them with financial independence.[5] Such indications of friendship and artistic collaboration provide an antidote to the many stories of gendered prejudice that appear elsewhere in the show.

While Katherine Read fell into obscurity after her death, she was well known in her own time. Her popularity is evidenced by the circulation of a mezzotint print after her pastel (Fig. 4), an impression of which is also in the Katrin Bellinger Collection. James Watson’s printed version of Miss Helena Beatson would have provided buyers with a more affordable version of the image and suggests that it reached a wider audience. This points to another leitmotif that recurs throughout the exhibition: that of the culpability of historians, critics, and art institutions in the dismissal of women artists and their subsequent need for “rediscovery” today. Reattributions abound in the show; most notably, perhaps, in the case of Artemisia Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders, which was catalogued as “French School” until 2023 (Fig. 5).[6] Read’s work has also been frequently misattributed to her male contemporaries, including Jean-Etienne Liotard, Joshua Reynolds, and Anton Raphael Mengs.[7] Such moments of rediscovery highlight the continued importance of organizing exhibitions devoted to women artists, even decades after the rise of feminist art history.

The Artist at Work collection holds significant potential for ongoing research into women artists in Britain and beyond. It is often through portraits or studio scenes that a particular woman’s artistic practice can be uncovered, especially if they did not sell their art or exhibit publicly under their own name. Such images also expose the artistic and personal networks through which women artists were able to thrive and situates them accurately in their historical contexts. Many of these works can now be explored together on the website under the theme “Women Artists.” In this context it is also worth mentioning the website of AWARE (Archives for Women Artists Research and Exhibitions), which offers a freely accessible and ever increasing wealth of research on women artists’ biographies, both historical and contemporary.

The exhibition catalogue is also available from Tate’s website.

Notes

[1] Tabitha Barber and Tim Batchelor, eds., Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 (London: Tate Publishing, 2024).

[2] For more on Read, see: Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, online edition, http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/Read.pdf#search=%22read%22

[3] Barber and Batchelor, Now You See Us, 85.

[4] See Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, online edition, http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/Beatson.pdf

[5] Barber and Batchelor, Now You See Us, 56.

[6] Barber and Batchelor, 27.

[7] Barber and Batchelor, 56.

Fig. 1: Mary Beale, Self-portrait as Artemisia, c. 1675, oil on sacking. West Suffolk Heritage Service.

Fig. 2: Louise Jopling, Through the Looking-Glass, 1875, oil on canvas. Tate.

Fig. 3: Katherine Read, Miss Helena Beatson, 1767, pastel. Katrin Bellinger Collection.

Fig. 4: James Watson, Miss Helena Beatson, 1768, mezzotint. The British Museum.

Fig. 5: Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders, c.1638-40, oil on canvas. Royal Collection Trust.

Reflections on Connecting Worlds: Artists and Travel, in Dresden

The world is a book and those who do not travel read only one page.

― St. Augustine

Nothing can be compared to the new life that the discovery of another country provides for a thoughtful person. Although I am still the same I believe to have changed to the bones.

― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey (1816–17)

The international loan exhibition Connecting Worlds: Artists & Travel realised by the Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (SKD) in collaboration with the Katrin Bellinger Collection closed its doors on 8 October 2023. Hosted in the spacious galleries of the Dresden Residenzschloss the dynamic display of over 120 works, primarily drawings and prints, was conceived to take visitors on a journey across different historical periods and geographical contexts. It relied on the unique power of works on paper to bridge distances and enable new connections. From the Renaissance to the nineteenth-century, from Albrecht Dürer’s journeys to those of the young Nazarenes and beyond, the selected drawings, sketchbooks and prints revealed experiences made on the road, telling of personal aspirations, friendships and exchanges nourished by travel. We selected most of the works from the rich holdings of the SKD and combined them with a substantial group lent by the Katrin Bellinger Collection. In addition, thanks to the generosity of colleagues and lenders we were able to supplement our two collections with a number of remarkable loans from institutions in Germany, Switzerland and the UK.

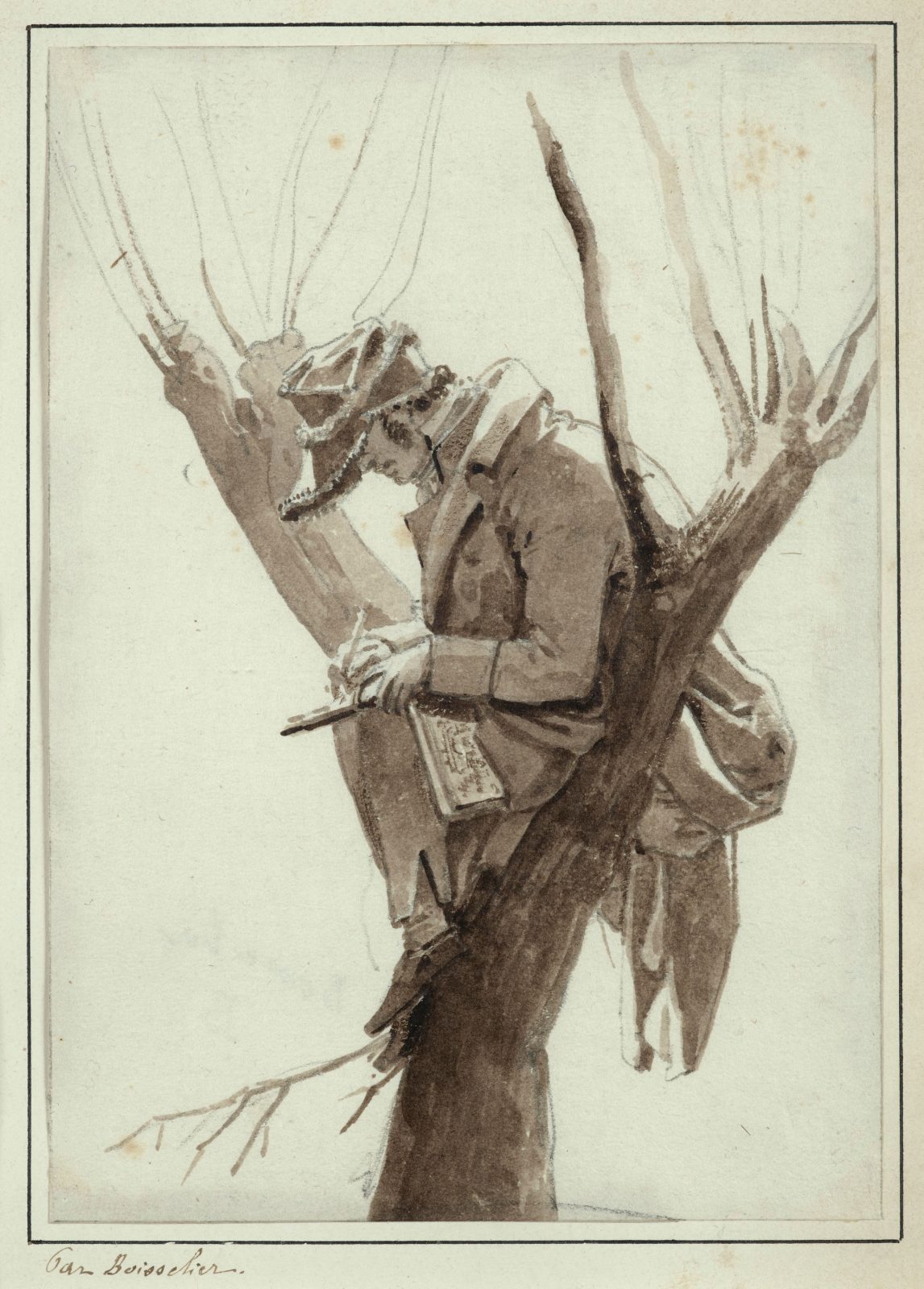

The loans from the Katrin Bellinger Collection included small sketches of artists at work en plein air such as Lambert Doomer’s atmospehric drawing of a behatted draughtsman seen from behind (fig. 1), as well as larger watercolours like Thomas Rowlandson’s Artist travelling in Wales, and artists’ tools. A well-used portable paintbox/easel (fig. 2) and a refined watercolourist’s walking cane were amongst the most popular exhibits with visitors. Similarly admired was Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc’s masterful watercolour (fig. 3) showing the artist sketching the inside of a glacier while trapped in a crevasse – one of the tiniest self-portraits in the collection!

THE JOURNEY

While offering some insights into the exhibitions structure and key themes I wish here to mainly share my experience of working on the project for the past three years and reflect on this journey now that it has come to a close. I co-curated Connecting Worlds and co-edited the accompanying catalogue together with Stephanie Buck, Director of the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett. I first met and worked alongside Stephanie when she was Curator of Drawings at the Courtauld Gallery and it was a privilege to realize this exhibition with such an imaginative and forward-looking curator and champion of works on paper.

The project was only possible because we enjoyed Katrin Bellinger’s unwavering support and enthusiasm in seeing it realized. She encouraged our ambitious scope and the creative directions we pursued in wanting to recreate for our visitors the spatial and intellectual experience of being ‘on a journey’. This also entailed enlisting the collaboration of other essential members of our team, alongside the brilliant colleagues at the SKD, starting with Mark McDonald, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, who generously acted as curatorial advisor and was instrumental in helping us define the key role of prints as agents of change and exchange within the display.

Early in the project we realized that an exhibition focusing on travel could not unfold according to a prescribed path but would necessarily be open to individual discovery with each visit allowing for a new route and new connections to be made. This is exemplified by the role played by Pieter Coecke van Aelst’s Costumes and Manners of the Turks (1553). One of the most influential printed depictions of a journey, it is a series of ten woodcuts relating to the Flemish artist’s travels to Constantinople. We invited London-based artist duo Ben Langlands and Nikki Bell to imagine a new way of exhibiting these detail-rich prints. I had the pleasure of working with them on the exhibition Absent Artists, which they curated at Charleston in 2022, and was keen for our collaboration to continue. Having understood the crucial role that travel plays in their work and thinking I was delighted when they agreed to lend their 1999 neon sculpture Frozen Sky as well as contribute to the exhibition design. Their vision of a set of curved vitrines that would require visitors to consciously move in the space was to inform our use of the galleries more broadly (fig. 4).

The balance of dynamism and elegance in the display was in large part due to the contribution of the artist and designer Ines Beyer, whose thoughtful approach gave life to truly poetic passages. One of my favourite features was the tall vitrine where we displayed several sketchbooks, some open and some closed, to illustrate their material qualities as well as their functions (fig. 5).

The sketchbook as a portable and flexible tool was at the heart of the first section of the show, ‘On the Road’, focusing on the artist as traveller and the practice of working outdoors. This was followed by ‘Destination Rome’ which centred on the Eternal City as a dream destination for travellers, tourists and artists from the Renaissance to the 19th century. A different type of travel – travel of the mind – was highlighted in the third section, ‘Dresden’, which looked at the sumptuous collections assembled by the Electors of Saxony from the perspective of their interest and curiosity about the cultures of Turkey, India, China and Brazil as expressed in a variety of artifacts and images (fig. 6).

TRAVEL AND FRIENDSHIP

Collaboration and sharing of expertise are at the heart of many successful exhibitions but in the case of Connecting Worlds their importance took on further meaning. Ever since we started brainstorming on the core themes for the show one emerged strongly for me: friendship. Companionship – or the longing for it – marks many artists’ experiences of leaving their home and pursuing new adventures.

Whether artists travelled in groups, like Johann Anton Ramboux and the Eberhard brothers, or encountered new friends at their destination, like Goethe and Angelica Kauffman who met in Rome, drawings often served to celebrate a bond. Portraits has a particular role to play. Some appear to have been spur of the moment, like Ernst Fries’ likeness of a young Camille Corot in a moment of contemplation in Cività Castellana, outside Rome (fig. 7). Others are formal commemorations, like Johann Georg Schütz’s spectacular watercolour depicting the entourage of Duchess Anna Amalia of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach in the gardens of Villa d’Este in Tivoli, lent by the Klassik Stiftung Weimar (fig. 8).

Friendship and memory come together in several of the sheet, especially in the section devoted to Rome as the meeting point for an international milieu of artists, patrons, Grand Tourists. For example, in the large sheet by Johann Anton Ramboux at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main (fig. 9), I found a ‘concealed’ self-portrait / group portrait. The main subject of the watercolour is the Feast of the Infiorata in the town of Genzano, outside Rome, but amongst the crowd of local onlookers, in the middle ground on the very left, we spot four Northern artists. With his peaked cap, satchel and sketchbook under his arm, Ramboux himself turns to gaze at the beholder. It was the presence of the artist, arguably motivated by the desire to crystallize the memory of that day, that called for the inclusion of this little-know and beautifully preserved sheet in the exhibition.

NEW PERSPECTIVES

As well as prompting new research, the project of Connecting Worlds inspired me to consider the types of questions we want to ask about the ‘Artist at Work’ collection. For example, what do we know about the experience of travelling as a woman and how is it reflected in specific works? The exhibition included famous women artists, such as the pioneering naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), who travelled from Amsterdam to Surinam in 1699 (fig. 10), and the cosmopolitan neoclassical painter Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807). But we also told the stories of less well-known early travellers, like the intrepid landscapist Louise Joséphine Sarazin de Belmont (1790–1870) who sought out the remote sceneries of the Pyrenees and was later captivated by the majesty of ancient Rome.

Moving forward we will continue to pursue thematic exhibition that may yield fresh insights into our holdings. Connecting Worlds has also strengthened our belief in the virtues of a transhistorical approach. With works that now span from the 14th century to today the potential for new connections is limitless. It was inspiring to see how in Dresden interventions by contemporary artists brought the dialogue between travel and image-making into the present, opening to new approaches to the historic pieces.

Although the exhibition is now closed, I am pleased to see that several forthcoming initiatives will further investigate the relationship between travelling and drawing. In March 2024, in particular, I look forward to continuing the conversation at the conference ‘Landscape drawing in the making: materiality – practice – experience, 1500–1800’ at the Fondazione Cini in Venice and at the study days hosted by the Salon du dessin in Paris on the theme of ‘Travel drawings’.

For those who missed Connecting Worlds: Artists & Travel or wish to revisit it, a virtual tour is available through the SKD’s website, and the richly illustrated exhibition catalogue offers boundless trails to pursue and be inspired by. As well as carefully researched catalogue entries it features essays by an international panel of experts addressing such topics as the uses of artist sketchbooks across time, encounters with the Ottoman world, travel as a topic for prints, travel and collecting at the Saxon court.

Exhibition catalogue

Stephanie Buck and Anita V. Sganzerla, eds., with the assistance of Jane Boddy, Connecting Worlds: Artists & Travel, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett, in association with Paul Holberton Publishing, 2023. Find it here

Fig. 1 Lambert Doomer, An artist seated by a tree, sketching, early 1660s, Katrin Bellinger Collection (cat. 18.1)

Fig. 2 Installation view. Photo: Chris Boulden

Fig. 3 Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, The artist sketching while trapped in a crevasse, 1870 (cat. 23)

Fig. 4 Installation view. Photo: Courtesy Langlands & Bell

Fig. 5 Installation view. Photo: Chris Boulden

Fig. 6 Installation view of 'Dresden' room with Frozen Sky (1999) by Langlands & Bell. Photo: Courtesy Langlands & Bell

Fig. 7 Ernst Fries, Camille Corot in Cività Castellana, 1826, Kupferstich-Kabinett, SKD, inv. C 1963-835. Photo: Herbert Boswank (cat. 55.1)

Fig. 8 Johann Georg Schütz, Duchess Anna Amalia of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach with her entourage in the gardens of Villa d’Este, Tivoli, 1789, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Graphische Sammlungen, inv. KHz/02075. Photo: Susanne Marschall (cat. 49)

Fig. 9 Johann Anton Ramboux, The feast of the Infiorata, Genzano, 1821, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, inv. 5691 Z (cat. 44)

Fig. 10 Jacobus Houbraken after Georg Gsell, Portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian, c. 1717, Kupferstich-Kabinett, SKD, inv. A 36998

A celebration of artists’ studios

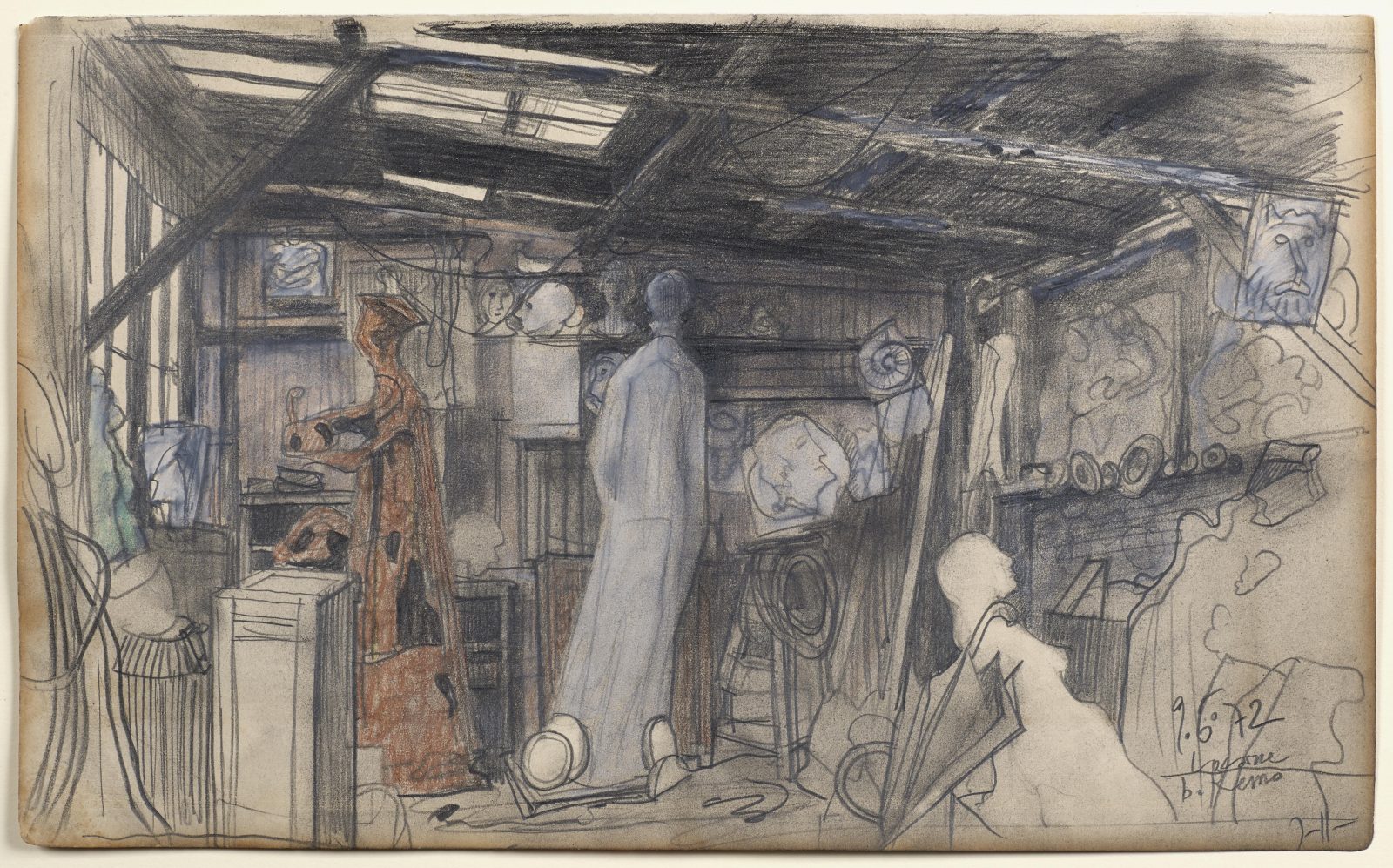

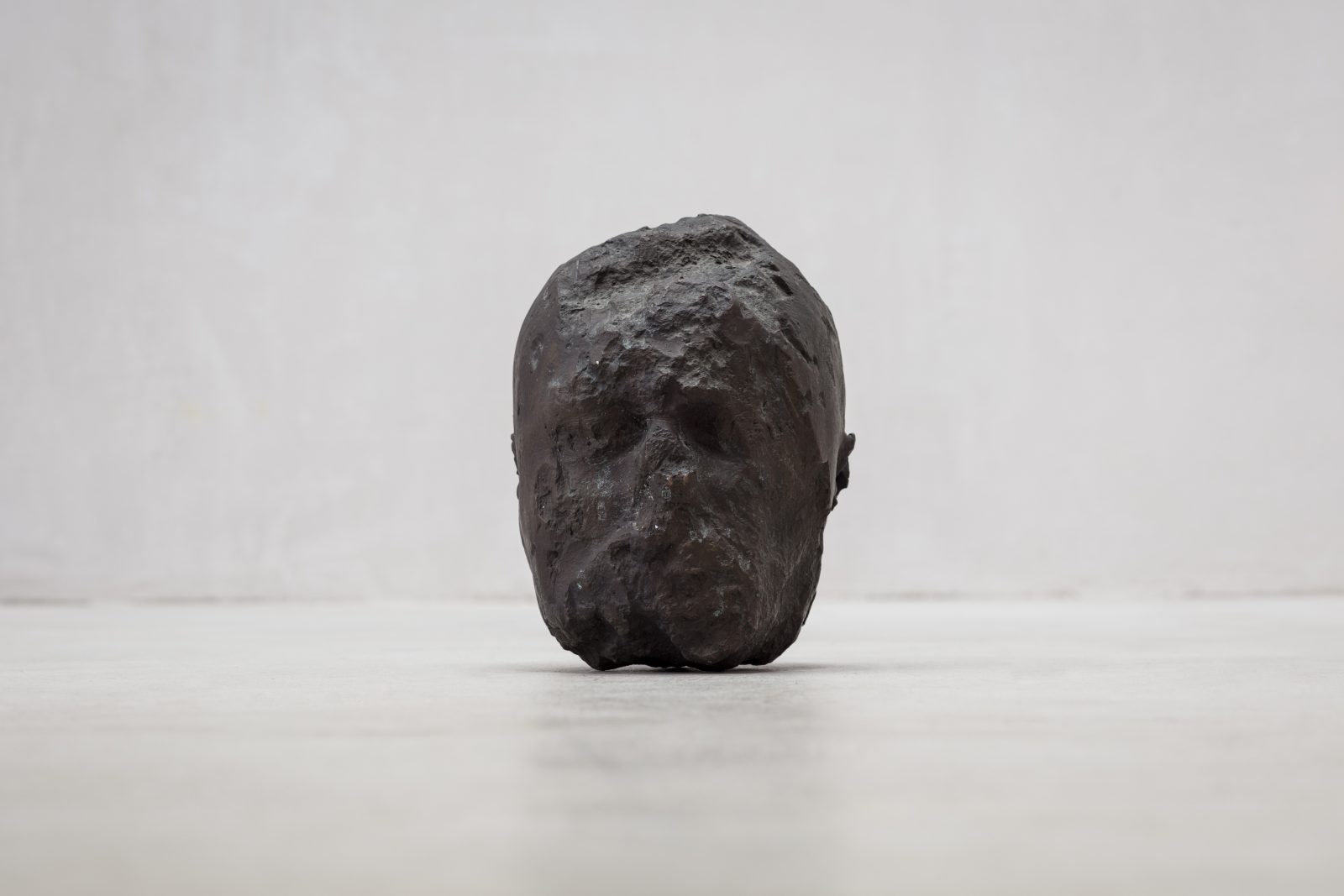

Less than two weeks remain to experience one of the most engaging exhibitions in London this Spring: A Century of the Artist’s Studio: 1920-2020 at Whitechapel Gallery. Curated by the Whitechapel’s Director Iwona Blazwick and her team, this extensive show features loans from public institutions and private lenders, including a carefully selected group from the Katrin Bellinger Collection comprising drawings, photographs, and a sculpture – Phyllida Barlow’s bronze cast of her paint brushes that she painted and prepared paint with (fig. 1).

Each visit to A Century of the Artist’s Studio is bound to be unique and that is part of the appeal of this rich exhibition. How long will you spend watching Paul McCarthy’s film Painter (1995), a visceral performance on the tribulations of the artist? Will you be drawn to Andy Warhol’s crowded and foil coated ‘Silver Factory’ or search for inner peace amongst the painted studio interiors of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham and Paul Winstanley? Some works might be familiar, like Martha Rosler’s seminal film Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), but most will be new discoveries for many. One of the show’s revelations for me was self-taught artist Maud Lewis (1901-1970) who transformed her humble shack in Nova Scotia with joyful nature-inspired decorations, wonderfully naïve and personal.

The rooms are constellated with works that will stimulate visitors to think about the significance of the studio as a ‘space of one’s own’ for both male and female makers. Another loan from the Katrin Bellinger Collection and one of the first exhibits to greet visitors even before they cross the glass doors to the gallery is Antony Gormley’s drawing of a man painting his own shadow, titled The Origin of Drawing VIII (fig. 2). An open appropriation of the story from Pliny the Elder explaining that painting was born when a woman outlined the shadow of her departing lover on the wall (so as to preserve his image), its presence here invites reflection on gender stereotypes around the myth of the artist. On the same wall hang two works by Lisa Brice whose representations of women in the studio challenge the assumption that the artist is always male (fig. 3).

The dialectic between different approaches to the spaces where art is made continues in the studio corners, informative and evocative thanks to the right balance of objects and traces of the artist’s creative process. I particularly enjoyed the Henri Matisse corner, with the African kuba textiles that he bought in antique shops or on his travels, and that served as both decorations and props. The studio of Kim Lim (1936-1997) also reflected her travels. In the show, her minimalist maquettes are set against the backdrop of her studio wall where she pinned photographs alongside found objects and tools. Working from a studio in her home Kim combined her career as sculptor and printmaker with family life – an arrangement that will resonate with many.

Fig. 1 Phyllida Barlow, untitled: paintsticks; 2017, 2017, 11 bronze sticks, maximum length 86 cm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2017-043

Fig. 2 Antony Gormley, The Origin of Drawing VIII, 2008, carbon and casein, 190 x 273 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2018-054

Fig. 3 Lisa Brice, Untitled, 2019, oil on trace, 419 x 296 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2019-063

Pastellists at work

A recent visit to La Maison du Pastel in Paris, the oldest pastel manufacturer in the world, inspired me to look afresh at the Katrin Bellinger Collection’s holdings in the medium and to consider the intersection between the art of pastel and depictions of artists at work.

Artists’ self-portraits in pastel are amongst the most iconic works of the eighteenth-century. Think of Rosalba Carriera’s Self-portrait as an allegory of Winter, c. 1745, or Jean-Etienne Liotard’s eccentric Self-portrait in Turkish costume, c.1746 [1]. Indeed, pastel proved particularly appropriate to the rendering of the softness of skin, making it exceptionally suited for portraiture. After a period of neglect during the ancien régime, it was in the late nineteenth century that the medium received a new lease of life, with the Impressionists celebrating its luminosity and immediacy.

A notable example from the Katrin Bellinger Collection is a striking self-portrait by Maurice Eliot (1862-1945), not a household name nowadays but a well-regarded pastellist at the turn of the nineteenth century (fig. 1). Here, we see the artist as if interrupted while working on a large canvas, which bears the preliminary outlines of a landscape. At once direct and mysterious, this great work is perhaps one of his most accomplished inventions beyond his preferred subject of views of the French countryside, much in the vein of the Impressionists. Just a year earlier, Eliot employed a more conventional yet effective style when depicting his friend, Charles Leandre (1862–1934), at work in their shared Parisian studio (fig. 2).

Less than a decade earlier, in 1878, Henri Roché, a man of science with a keen interest in art, took control of La Maison du Pastel, marking a pivotal point in its 300-year history. Roché’s close relationship with several contemporary artists drove his commitment to meeting their needs for reliable and solid colours in a wide range of luminous shades. Today, Isabelle Roché, distantly related to Henri, is at the helm of the firm. Since 2000, she has passionately cultivated the Maison’s unique heritage, ensuring its continued activity. It was fascinating to learn the history of the Maison from her and her close collaborator, Margaret Zayer, who oversees product development and formulation.

Entirely hand-made following the same processes adopted in the eighteenth century, the Roché pastels continue to inspire artists near and far. A name worth remembering here is that of Sam Szafran (1934-2019), a staunch champion of the Maison and its products.

Szafran’s dizzying perspectives, including depictions of his cavernous studio where multiple trays of pastels take centre stage, spoke to a niche audience and were only given due recognition posthumously (fig. 3). This renewed attention may have come thanks to the recent resurgence of scholarly and technical interest in pastel. A current exhibition at the Achenbach Foundation in San Francisco offers fascinating insights into the use of pastels from the Renaissance to today (open until 13 February 2022). With its ductile materiality and distinctive challenges, pastel allows its practitioners to cross the boundaries between drawing and painting. It also adapts in unique ways to the demands of different aesthetics and expressive quests. A case in point is Paula Rego (b. 1935), whose daring large-scale pastels were at the heart of a recent retrospective at Tate Britain.

Rego’s radical approach to pastel is embedded in a long tradition of women’s mastery of the technique, running from the sixteenth century up until today. A personal favourite in the collection is Annie Leibovitz’s photograph of an assortment of pastels that belonged to Georgia O’Keeffe (fig. 4). While her vivid pastels are a less well-known aspect of her oeuvre, O’Keeffe returned regularly to the medium and even made some of her pigment sticks herself. [2]. “Seeing them, you really have the sense that she held and used them. They are the colours of New Mexico: the reds are the sand in the hill, the blues are the sky.” [3] Thus, this celebration of pastel’s tactile beauty is also a poignant portrait, in absentia, of the American artist.

Explore related themes: Artists tools; Women Artists

Notes

[1] Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv. nos. Gal.-Nr. P 29 and Gal.-Nr. P 159.

[2] Leibovitz visited O’Keeffe’s homes in Northern New Mexico as part of her project Pilgrimage (2009-2011), in which she explored portraiture without people but through their memory-filled spaces and objects. The pastels in the photograph are in the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

[3] Annie Leibovitz interviewed by Sarah Phillips, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/nov/22/annie-leibovitz-best-shoot-okeeffe

To learn more see also: www.pastellists.com

Fig. 1 Maurice Eliot, Self-portrait, 1887, pastel on canvas, 61 x 50 cm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2019-060

Fig. 2 Maurice Eliot, Portrait of Charles Leandre, 1886, pastel on canvas, 27 x 22 cm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2017-022

Fig. 3 Sam Szafran, Untitled, 1971, pastel on paper, 119.4 x 80.3 cm, New York, MoMA, inv. 123.1974

Fig. 4 Annie Leibovitz, Georgia O’Keeffe’s pastels, from ‘Pilgrimage’, 2010, archival pigment print, 34.29 x 50.8 cm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2012-023

The Human Touch at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

After a year during which physical contact has been suddenly precluded to us and we have all had to adapt to virtual or distanced encounters like never before, a museum exhibition focusing on the cultural history of the sense of touch is bound to make a mark.

Curated by Elenor Ling, Curator of Paintings, Drawings and Prints, and Suzanne Reynolds, Curator of Manuscripts and Printed Books, the Fitzwilliam Museum’s interdisciplinary show The Human Touch: Making Art, Leaving Traces features objects spanning four millennia of human experience and tells the story of how touch, specifically human touch, has defined perceptions and beliefs, inspired scientific advancements, and fascinated artists and intellectuals. Drawing primarily from the rich heritage of Cambridge University and its museums, the show also includes some important loans from public and private collections, with a considerable group coming from the Katrin Bellinger Collection.

The objects included in the exhibition tell of the multi-layered history of touch. Amongst the topics explored is that of the physical interaction with works of art, either in the process of their creation, or at a later phase of fruition. This aspect is amply demonstrated through examples of manuscripts that show the signs of their use and their readers’ different ways of ‘making their mark.’

At the heart of the display is a section devoted to the hands of the artist, where the hand as the painter’s or sculptor’s primary tool intersects with the hand as object of investigation. In the process of selecting possible loans to the show, in dialogue with the curators and with Katrin Bellinger, we each shared insights into the complexity of the role of touch in art. And it was a pleasure to see how the selected works were incorporated into the exhibition’s intertwining narratives.

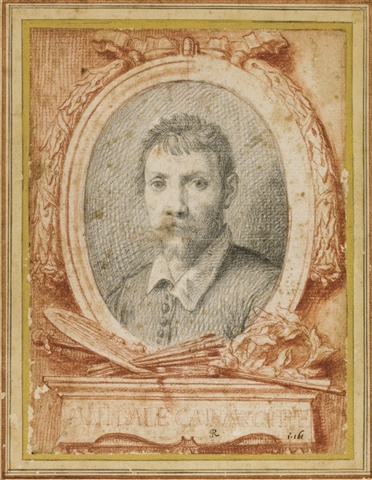

A study of hands sharpening a quill by Agostino Carracci (1557–1602) seems to teach us a double lesson. It is a beautiful example of Agostino’s draughtsmanship while also demonstrating the technique used to prepare one of the fundamental artists’ tools. The didactic aim was at the origin of this sheet, and it was engraved by Luca Ciamberlano for one of the plates of the instructional drawing book La scuola perfetta per imparare a disegnare tutto il corpo humano…, c. 1620, Rome (Fig. 1).

Amply featured in artists’ manuals, hands are notoriously hard to draw or paint. A challenge that will never cease to intrigue. A small intimate oil sketch by contemporary French artist Louis Wade (not in the exhibition) transports us to the heart of the studio by homing in on a crop of the painter’s hands intent in wiping his paintbrushes (Fig. 2).

A drawing by Edgar Degas (1834–1917) attests to his early attempts at mastering the difficult task of drawing his own hands at work, which, as for Wade, would have entailed the use of a mirror (Fig. 3). This subtle portrayal is also a touching testimony of Degas’ admiration for the old masters—the pale pink prepared paper is reminiscent of the tone favoured by Raphael for his metal-points. Degas collected drawings of hands by fellow artists and owned a cast of the hand of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whom he revered, holding a pencil. [1] As well as testimonies of their skills, the painted or sculpted hands of famous artists could also come to be perceived as portraits of sorts.

A recent acquisition, Rebecca Ackroyd’s Scratching the surface (not in the exhibition), shows a hand, writing in a diary. While aligned with the artist’s uncanny penchant for disembodied limbs, it also places the accent on the subjective power of the hand and its ability, through the acts of drawing or writing, to dig beyond the appearance of things (Fig. 4).

It was interesting to see works from the Katrin Bellinger Collection included in other sections of The Human Touch apart from that devoted to the hand of the artist. A Dutch painting, Pygmalion and Galatea is part of a section exploring myths that call into play the power of touch and its moral implications. Here, Pygmalion does not place his hand on the beautiful statue he has created but instead wistfully presents his beloved with a bunch of flowers. The scene is centred on the physical encounter between the real flowers and the stony sheaf of wheat in Galatea’s hand. The expert hand of the sculptor is further alluded to in the tools scattered around him (Fig. 5).

A final section on touch and belief includes four sets of Marianne Raschig (1879–c.1939)’s hand-prints of artists. The renowned German palmist collected over 2000 such handprints of musicians, artists, writers, and scientists. Signed and dated by each individual, including prominent figures in the cultural panorama of 1920s Berlin, they stand as compelling testimonies of direct contact, of a time and place, as well as being instruments through which Raschig developed her theories. Palm readers believe that our hands have a series of ‘lines and ‘mounts’ which reveal our personality traits and can even help predict our future. The left handprint of German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) was also chosen as poster image for the show and features on the cover of the beautifully illustrated catalogue, with essays by Jane Munro and the two curators contextualizing the various strands that interlink in this thought-provoking exhibition (Fig. 6).

The Human Touch: Making Art, Leaving Traces is open at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, until 1 August 2021

EXPLORE RELATE THEME: THE ARTIST’S HAND

Note

[1] Now in the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris; see Elenor Ling, Suzanne Reynolds and Jane Munro, The Human Touch: Making Art, Leaving Traces, exhibition catalogue, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 2021, p. 53, fig. 41.

Fig. 1 Agostino Carracci, Study of hands sharpening a pen, c. 1600, pen and brown in, brown wash, on paper pricked for transfer, 107 x 202 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2018-012

Fig. 2 Louis Wade, Study of the artist’s hands (cleaning his brushes), 2017, oil on wood, 200 x 250 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2019-007

Fig. 3 Edgar Degas, Study of the artist’s hands, with other studies, c. 1835-54, graphite on pale pink laid paper, 312 x 234 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2018-015

Fig. 4 Rebecca Ackroyd, Scratching the surface, 2020, epoxy resin, 290 x 190 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2020-017

Fig. 5 Dutch School, c. 1670, Pygmalion and Galatea, oil on panel, 380 x 510 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 1995-048

Fig. 6 Marianne Raschig, Hand-prints of Käthe Kollwitz, signed 16 June 1925, ink on paper, touched with graphite, 210 x 165 mm (each), Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2013-017

A UK first: Artemisia Gentileschi at the National Gallery

The National Gallery’s exhibition Artemisia was one of the long-awaited shows of 2020 and no postponement or interruption dampened the well-deserved excitement that built around it. The London institution’s significant acquisition in 2018 of Artemisia Gentileschi’s (1593–1654) Self-portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (fig. 1), and the lack of a monographic exhibition devoted to her in the UK, contributed to impress on curator Letizia Treves the necessity for one such effort. The show featured thirty-six paintings covering the full span of Gentileschi’s peripatetic career and including many of her best-known and best-preserved works [1].

Forming a diverse group within her oeuvre, Artemisia’s self-portraits blurred the boundary between self-promotion and artistic practice, and her insertion in many of her paintings was noted by her contemporaries, who would have appreciated both her wit and her business-acumen. This inspired me to focus here on images of Artemisia, either by herself or by others, to consider their significance both within and beyond the span of her career.

A Roman artist

Born in Rome, Artemisia’s only teacher was her father, the celebrated painter Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639). As a woman she was not allowed to leave her home unsupervised and wander freely around the street, churches and palaces of the Holy City (she was also responsible for her three younger brothers). In spite of these limitations, Artemisia Gentileschi quickly developed into a competent painter, so skilled to inspire her father’s pride. Her earliest signed and dated work, the Suzanna and the Elders (Schloss Weißenstein), made when she was 17 years old, is an accomplished and original retelling of the familiar moral tale, from a female perspective.

The course of her life was drastically diverted when one of father’s associates, the well-connected painter Agostino Tassi, raped the young Artemisia, later promising to marry her. A promise he broke, leading to Orazio pressing charges against Tassi. The trial that followed was a public affair and resulted in Tassi’s sentencing to exile – a punishment that was never enforced. Soon after the trial it was Artemisia who left her native city in search of a fresh start, having married Pierantonio Stiattesi, a modest Florentine painter.

Florence 1613-1620

In Florence, Gentileschi becomes the first female member of the prestigious Accademia del Disegno. Probably soon after her arrival she executed her first known self-portrait, fashioning herself as a female martyr (fig. 2). The motif of the cloth loosely wrapped around the figure’s head helps to characterize the protagonist as a historical character while also relating to Artemisia’s own involvement with theatrical dress-up: she is said to have performed the role of a gypsy.

In her now famous self-portrait in the guise of the 4th-century Christian martyr, Saint Catherine of Alexandria (see fig. 1), she continued to play with self-fashioning and to blur the boundary between self-portraiture and historical depiction, by combining Catherine’s crown with the piece of fabric loosely wrapped around her head by way of a signature. Legend describes Saint Catherine as a philosopher and daughter of a prince of Egypt, who was tortured on the spiked wheel for refusing to renounce her Christian faith. Her martyrdom is symbolized by the palm branch she holds in her right hand.

One of the highlights of the show was the opportunity to see Artemisia’s four Florentine self-portraits in a glorious line-up. Technical analysis recently carried out by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence, has shown that the National Gallery and Uffizi (fig. 3) versions of Saint Catherine are based on the same preparatory drawing or cartoon, and that this also constituted the starting point for the striking Self-portrait as a Lute Player in Hartford (fig. 4).

Back in Rome: Artemisia’s hand

Despite the demand for her paintings in Florence and her attempts to be seen as an artist of Tuscan lineage (she adopted the surname Lomi, after her paternal grandfather, a goldsmith), Artemisia was forced back to Rome by financial hardship. She also lost three of her five children. Comfort came, at least in part, from her love affair with the Florentine nobleman Francesco Maria Maringhi. The discovery in 2011, in the Archivio Storico Frescobaldi in Florence, of a group of letters written by Artemisia and her husband to Maringhi, reveals him as not only her lover, but also a confidant, intermediary and financial supporter for the rest of her life (the two met in Florence when they were both 24 years old).

Back in Rome from early 1620, Artemisia’s success grew. She became a sought-after portraitist and continue to develop her unique brand of Caravaggism. Together with the attention of patrons, the artistic community’s fascination with Artemisia as woman and artist developed, as attested by the many depictions of her likeness in paintings, drawings, prints and medals. Her contemporaries may have been aware of the misadventures of her youth but did not mention them. There was so much more about Artemisia deserving of praise: her wit, her talent, her beauty.

Simon Vouet’s painting of circa 1623-26 (fig. 5) portrays her as both elegant and committed to her trade, with a palette and brush in her left hand and a toccalapis (chalk holder) in her right. The prominently displayed gold medallion features a mausoleum, a witty play on words used to identify the illustrious sitter by referring to her namesake, Artemisia of Halicarnassus (d. 350 BC), who built the famous Mausolus, one of the wonders of the ancient world.

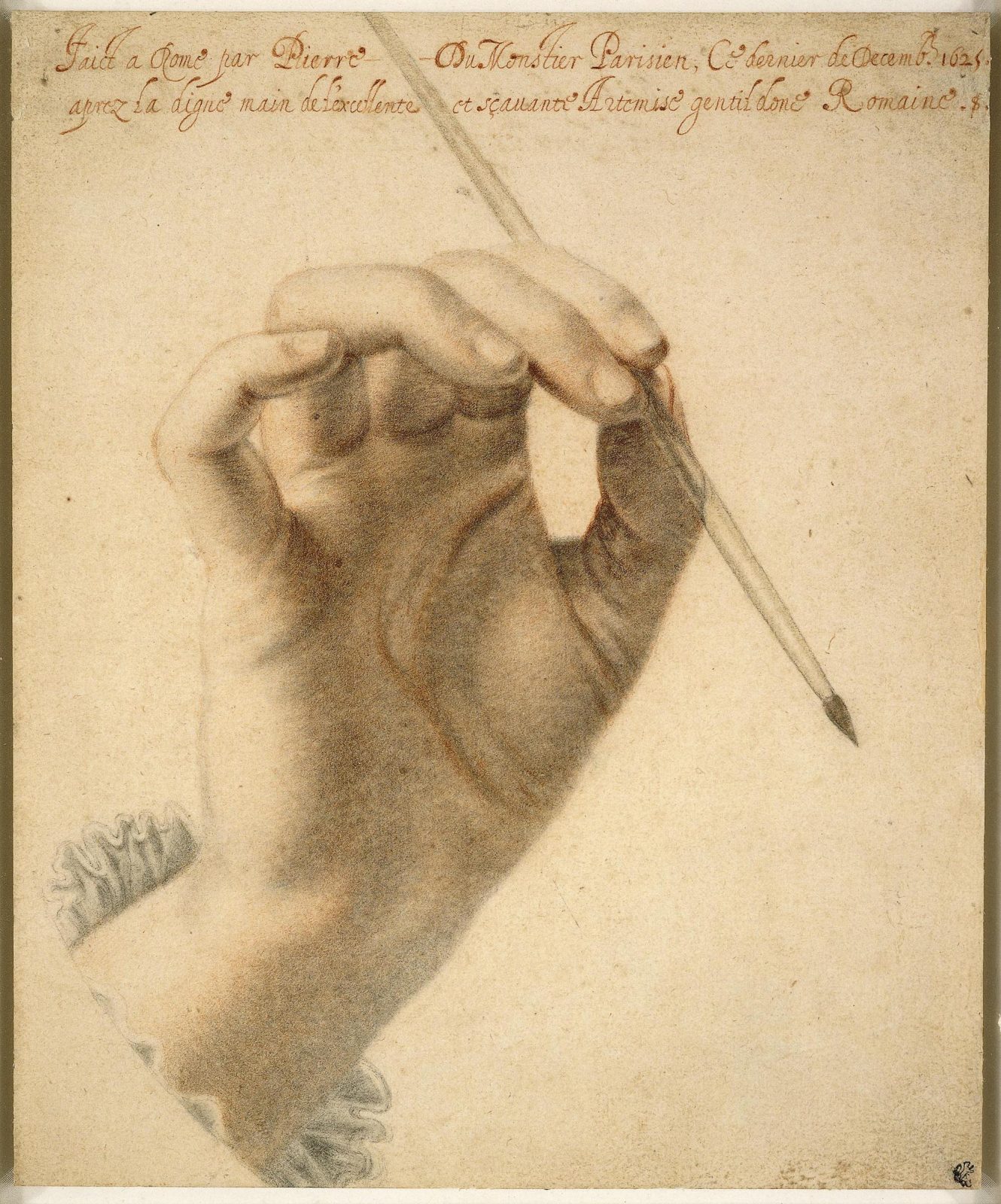

Not far from Vouet’s large portrait, visitors to the exhibition would encounter a chalk drawing by Pierre Dumonstier II, who, like Vouet, met Artemisia in Rome. This is a symbolic portrait of the artist, as it shows Artemisia’s right hand elegantly holding a brush (fig. 6). The inscription on the verso of the sheet translates as ‘The hands of Aurora are praised and renowned for their rare beauty. But this one is a thousand times more worthy for knowing how to make marvels that send the most judicious eyes into raptures.’

Venice, Naples, London: The spirit of Caesar in the soul of a woman

Her notoriety was not enough to guarantee Artemisia’s life in Rome. Instead, after a brief stint in Venice where she painted her majestic Esther before Ahasuerus (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), she would be based in Naples for the rest of her life while constantly seeking the elusive support of foreign noble patrons.

Her short yet important sojourn in London in the late 1630s was celebrated in the last room of the National Gallery’s display. In London, she had the chance to reunite with her father and briefly collaborate with him on his last big commission, the ceiling paintings of the Queen’s House, in Greenwich (now at Marlborough House in London).

It was probably during her stay in London that Gentileschi painted one of her most iconic works, the Self-portrait as Pittura (fig. 7), “the quintessential Baroque version of the Allegory of Painting” [1]. It is based only in part on Cesare Ripa’s description in the Iconologia (fig. 8), note the gold chain with a pendant mask which stands for imitation, and the unruly locks of dark hair which signify the frenzy of the artistic temperament. By then in her 40s, Artemisia imbued her allegorical self-portrait with the qualities she considered vital to her art: her Pittura is an energetic maker, not a static symbol.

Despite achieving fame and recognition in her lifetime, Artemisia was long overlooked until her ‘rediscovery’ initiated by feminist art scholars in the 1970s. Experts have long grappled with the relationship between her personal experiences and the content of her paintings – often focusing on resolute female heroines. By focusing on her oeuvre through particularly outstanding examples, the National Gallery’s show succeeded in shifting our attention towards her skills and talents as a Baroque artist, without losing sight of her unique story and struggles.

Building on the momentum of the London show the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford has announced its first exhibition solely dedicated to Italian women artists, entitled By Her Hand: Artemisia Gentileschi and Women Artists in Italy, 1500–1800 (September 30, 2021 – January 9, 2022).

Explore related themes: Women artists, Allegories of the arts

Note

[1] Exhibition catalogue, Artemisia, National Gallery, London, 2020, ed. Letizia Treves.

[2] Mary D. Garrard, ‘Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting’, The Art Bulletin, vol. 62, no. 1, 1980, p. 106.

Fig. 1 Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1615-17, oil on canvas, 71.4 × 69 cm, National Gallery, London

Fig. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-portrait as a female martyr, c. 1615, oil on canvas, 32 x 24.7 cm, private collection

Fig. 3 Artemisia Gentileschi, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1615-17, oil on canvas, 77 x 62 cm, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence

Fig. 4 Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-portrait as a Lute Player, 1615-17, oil on canvas, 30 x 28 cm, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut

Fig. 5 Simon Vouet, Portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi, c. 1623-25, oil on canvas, 90 × 71 cm, Palazzo Blu, Pisa

Fig. 6 Pierre Dumonstier II, Right hand of Artemisia Gentileschi holding a brush, 1625, black and red chalk, 219 x 180 mm, British Museum, London, inv. no. Nn,7.51.3

Fig. 7 Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura), about 1638-9, oil on canvas, 98.6 x 75.2 cm, Royal Collection Trust / HM The Queen, inv. no. RCIN

Fig. 8 La Pittura, from Cesare Ripa, Iconologia, ed. 1603

Reflections on Young Rembrandt in Oxford

The fascination with artistic genius is one many of us share. When admiring a work of art, we may find ourselves contemplating the origins of its maker’s talent. We may wonder where and from whom they learnt their craft, if they were precocious, self-taught, solitary, eccentric. Taking its lead from such lines of enquiry, the exhibition Young Rembrandt, which closed last month at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, transported audiences to the origins, early struggles and successes of the Dutch master’s career and oeuvre.

More specifically, Young Rembrandt, curated by Professor Christopher Brown CBE, An Van Camp and Dr Christiaan Vogelaar, considered the first ten years of Rembrandt’s career, 1624-1634, from his early beginnings in his native Leiden to the year he sat up his own workshop in Amsterdam.

After its first leg at the Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden, the show opened in Oxford and managed to have a successful run, in spite of the disruptions caused by the pandemic. The Ashmolean Museum’s curator, An Van Camp, devised an inspired hang with a combined chronological and thematic approach, juxtaposing works in different media in order to cast new light on Rembrandt’s daring technical experimentations.

To me, the opportunity offered by the exhibition and accompanying catalogue was two-fold. On the one hand, a strikingly diverse array of early works by Rembrandt were brought together and compared. On the other, the first decade of his artistic output was contextualized through a selection of paintings and graphic works by closely connected artists, notably his friend and colleague, Jan Lievens (1607–1674), and one of his earliest pupils, Gerrit Dou (1613-1675). In what follows I will consider these two lines of enquiry with specific focus on Rembrandt’s early self-portraits.

Young Rembrandt in the picture

Upon entering the exhibition space, visitors were greeted by the man himself. A feature wall presented a bold hang with three self-portraits made in c. 1628-29: a drawing, a painting and an etching. This opening group eloquently introduced and framed the whole display. The three self-portraits are among Rembrandt’s most iconic works but seeing them together and up close still felt like a revelation.

The Self-portrait with mouth open (Fig. 1), his earliest drawn self-portrait, is a study of expression and chiaroscuro. It is spontaneous and painterly and much smaller than the Self-portrait bare-headed, a rare etching of which only two impressions are known (Fig. 2). In no other print has Rembrandt attempted such experimentation: alternating the etching needle with a quill or reed pen, thus obtaining split lines, undoubtedly harder to ink. Although this technique added further unpredictability to an already error-prone medium, we can see what Rembrandt was trying to achieve. He wanted to make prints that looked like drawings. Indeed, some of his freer etchings emulate the spontaneity of a sketchbook page (Fig. 3).

At the centre of the wall stood another masterpiece: the small arresting panel from Munich (Fig. 4). Although he cast his forehead and brows in almost complete shadow, Rembrandt’s piercing eyes are staring directly at us. The thick impasto of his white collar is worth lingering on as an anticipation of his rough handling of oil paints.

Master of disguise

As well as highlighting Rembrandt’s commitment to technical experimentation, the three opening self-portraits also brought into focus his fascination with human nature and with the human face. If he did begin by portraying his own face for practical reasons, he certainly appreciated from early on the ‘marketability’ of his likeness, whether ‘natural’ or disguised. Rembrandt’s fondness for dress up and camouflage went hand in hand with his continuous investigation of the essence of his own humanity, so that many of his prints from this period blur the boundary between character study and portraiture.

In Beggar seated on a bank, 1630, we recognise Rembrandt’s features and are reminded of his minute studies of expressions (Fig. 5). The contrast with Self-portrait in a soft hat and patterned cloak, made just a year later, could not be stronger (Fig. 6). In this, his first official self-portrait, the artist assumes the guise of a gentleman. He even gives himself a lovelock, a long tress of hair draped over his left shoulder, fashionable among Continental aristocrats.

Begun in Leiden and completed in Amsterdam, the Self-portrait in a soft hat and patterned cloak went through 15 states. Of these, only the last two are signed ‘Rembrandt’, indicating that he had by that point settled in Amsterdam and intended to be known by his first name only, following the tradition of Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo and Raphael.

‘Astonishing beginnings’

Considering the associations of his signature, manipulating his appearance, and modelling himself after such successful cosmopolitan artists as Peter Paul Rubens, were all manifestations of the young Rembrandt’s innate drive for success.

Equally determined was his close friend Jan Lievens. Less familiar to a UK public, Lievens received well deserved attention in the Oxford show, which featured, for instance, his dramatically lit Magus at a Table of c. 1631, from Upton House. [1] Famously, Rembrandt and Lievens made a strong impression on Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), secretary to the prince of Orange, who visited them in Leiden in October 1628. In his diary, Huygens wrote at length about the ‘pair of young and noble painters from Leiden,’ praising their ‘astonishing beginnings’ while also predicting Rembrandt’s overall superiority. [2] Although their paths would soon part, the Young Rembrandt exhibition and catalogue make a valuable contribution to our understanding of Rembrandt and Lievens’ seminal creative liaison.

Both young men studied with the same masters (Jacob van Swanenburg in Leiden and Peter Lastman in Amsterdam), although at different times, with Lievens always slightly ahead of Rembrandt. They probably shared a studio in Leiden, employed the same models, and would have studied each other’s likenesses. [3] Although no effigy of Lievens by Rembrandt survives, the young artist at work examining a panel on an easel, in the captivating pen and ink drawing at the Getty (Fig.7), if not Rembrandt, may be a young Lievens.

Visit Young Rembrandt – Online Exhibition here

Notes

[1] Oil on panel, 55.9 x 48.6 cm, Upton House, Warwickshire, inv. no. NT 446728.

[2] Young Rembrandt, exh. cat., Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 2020, p. 297.

[3] See Jan Lievens’s Portrait of Rembrandt, c. 1628, oil on panel, 57 × 44.7 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. no. SK-C-1598, www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-C-1598 (visited 22.12.2020)

Fig. 1 Rembrandt, Self-portrait with mouth open, c. 1628-29, pen and brown ink with grey wash, 127 x 95 mm, British Museum, London, inv. no. Gg,2.253

Fig. 2 Rembrandt, Self-portrait bare-headed: bust, roughly etched, 1629, etching, 182 x 156 mm, British Museum, London, inv. no. 1848,0911.19

Fig. 3 Rembrandt, Sheet of studies: head of the artist, a beggar couple, heads of an old man and old woman, etc., 1632, etching, 104 x 116 mm, state I/II, British Museum, London, inv. no. 1848,0911.187

Fig. 4 Rembrandt, Self-portrait, 1629, oil on oak panel, 155 x 127 mm, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, inv. no. 11427

Fig. 5 Rembrandt, Beggar seated on a bank, 1630, etching, 116 x 70 mm, British Museum, London, inv. no. F,5.126

Fig. 6 Rembrandt, Self-portrait in a soft hat and patterned cloak, 1631, etching and drypoint, 147 x 130 mm, state XIV/XV, British Museum, inv. no. F,4.9

Fig. 7 Rembrandt, An Artist in his studio, c. 1630, pen and ink, 205 × 170 mm, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv. no., 86.GA.675

Menzel or not?

Every collector of Old Masters is familiar with the pitfalls of changing attributions and in the field of drawings this is even more an issue as they are rarely signed. However, you would not expect this to be a problem with 19th century drawings and certainly not those by an artist such as Adolph von Menzel who frequently signed or monographed his drawings, and whose style after all is very recognisable.

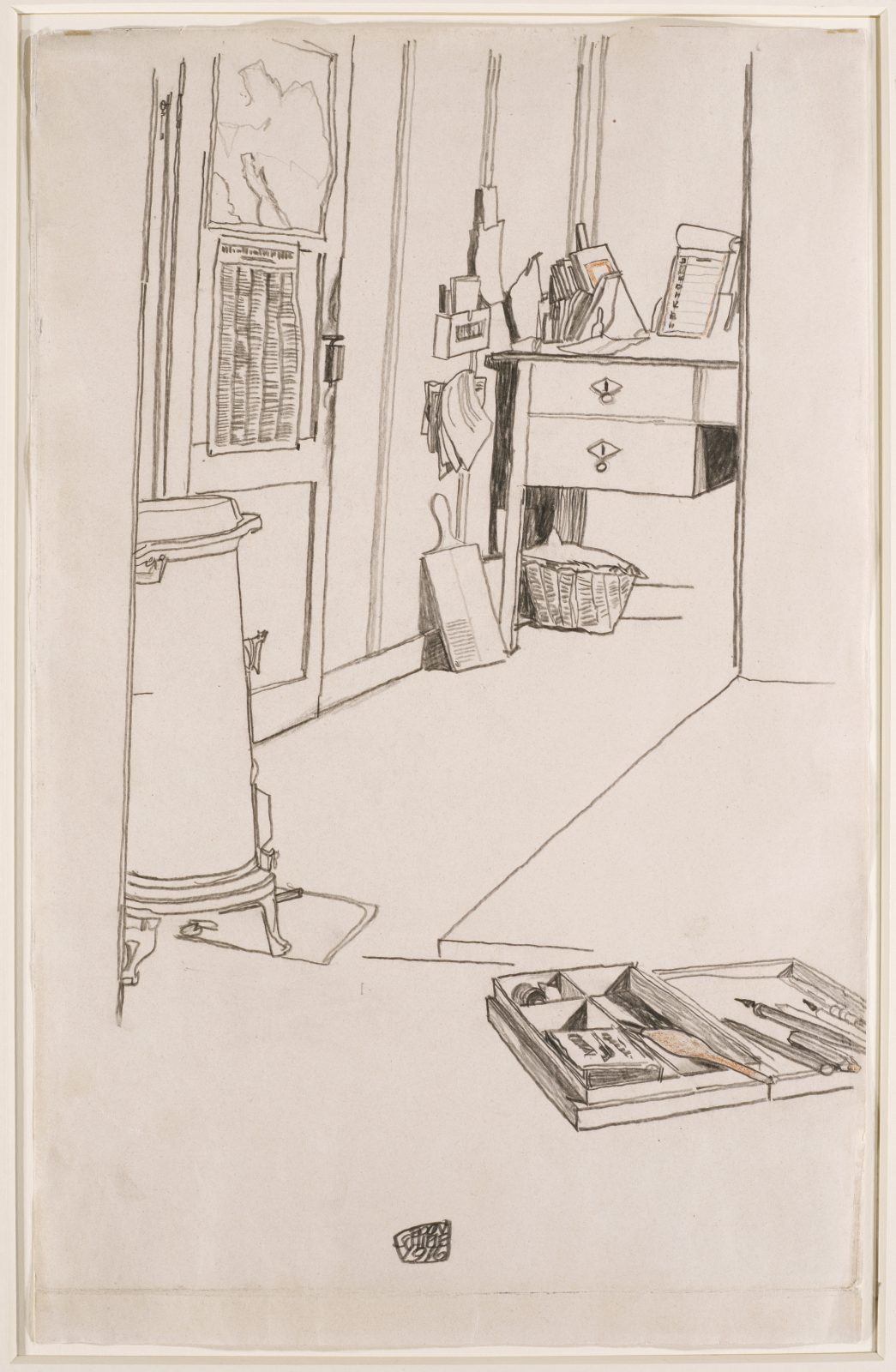

Nevertheless, I have a drawing in my collection where it is not at all clear if the drawing is by his hand even though it obviously shows Menzel in his studio (Fig. 1). What is painful is that I bought the drawing as by Menzel in an auction when it was accepted by the expert Marie Ursula Riemann-Reyher. I did wonder at the time because the drawing did not at all resemble anything else by the artist, but this was mitigated by a letter from Menzel on the back describing how the image illustrated him at work on this large commission in his temporary studio in Kassel, and it was also included and illustrated in the famous memorial exhibition in 1905, another certain indicator that was by his hand [1]. I very much wanted to believe this strong evidence despite my instinct because I was so keen to own a drawing by him that fits the theme of my collection. Are other collectors familiar with this phenomenon, when the desire to own something clouds your judgement?

So, if the carefully executed and tediously finished drawing is not by Menzel, could it be someone recording him in the studio?

Carl Johann Arnold, the son of Menzel’s friend Karl Heinrich Arnold and his only pupil, assisted him while he was working on the large cartoon of ‘Sophie von Brabant entering the city of Marburg with her son Heinrich.’ Young Arnold often drew Menzel while he stayed with his family but those drawings are always in pencil and stylistically quite different.

Claude Keisch has mentioned similarities to drawings by Johann Erdmann Hummel, a native of Kassel who taught perspective in Berlin, but it is highly unlikely that the 79- year-old artist would have been in Kassel exactly at this time [2]. Another fascinating idea Keisch has suggested is that the work could be a stylistic parody by Menzel of Hummel’s carefully finished interiors. Menzel is known to have done this kind of works in the context of his illustrations of the life of Frederick the Great but then it is surprising that there is no mention of his humorous intention in the attached letter.

I resolved my dilemma of owning either a drawing by Menzel or an interesting historic document by buying a drawing definitely by Menzel which further illuminates his stay in Kassel (Fig. 2). The amusing caricature was a gift to Carl Arnold’s sister and the inscription ‘who is still here’ refers to the fact that Menzel, rather than staying the planned eight weeks, remained with her family for eight months from August 1847 until March 1848. Many details refer to his much-extended stay which is supposed to lead “ad parnassum” to Apollo and the Muses. The other elements may well allude to the conversations in the Arnolds’ circle – “without spades” can symbolically stand for “without resentment” in the French card game – probably a suggestion to endure the exhausting presence of the artist, if possible, with good humour.

For me the acquisition of this drawing means that I can now put the work of ‘Menzel in his studio’ into context and tell a story which will, I hope, put my mind to rest about this acquisition.

On another occasion my yearning to own a Menzel drawing made me ‘cheat’ somewhat by buying a wonderful and typical sketchbook page in graphite showing an artist painting (Fig. 3), but when looking at the finished gouache it becomes clear that it is depicting a house painter and not an artist [3].

The most perfect example in my collection is a tiny drawing with a few touches of watercolour showing Menzel’s used brush (Fig. 4), and in that manner so unique to Menzel he transforms the ordinary into the sublime [4].

Notes

[1] Exh. cat. Adolph Menzel. Sonderausstellung zum Gedachtnis des Meisters. Leipzig, Kunstverein, at Museum der bildenden Künste, 1905 (according to label on backing board).

[2] Email communication, 26.5.2018 and 19.11.2020.

[3] D. Petherbridge and A. V. Sganzerla, Artists at Work, exh. cat., London, The Courtauld Gallery & Paul Holberton, 2018, no. 13, illustrated. This is a study for Menzel’s Beati possidentes (Happy owners), 1888, George Schäfer collection, Euerbach.

[4] C. Keisch and M. U. Riemann-Reyher, eds., Adolph Menzel. Briefe, Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2009, vol. 1 (1830 – 1855), p. 238, no. 221, illustrated.

Fig. 1 Adolph von Menzel (?), The Artist in his Studio, Kassel, 1847/48, watercolour, pen and black ink on cardboard, 175 x 137 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2012-015

Fig. 2 Adolph von Menzel, The Artist’s Glasses, 1847, pen and black and brown ink, 203 x 141 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2018-052

Fig. 3 Adolph von Menzel, Studies of a Man painting, 1888, graphite with stumping, 200 x 125 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2011-022

Fig. 4 Adolph von Menzel, The Artist’s Paint Brush, Zimmermann lead, grey-brown wash, watercolour, 63 x 100 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 1993-031

The whole world is Angelicamad

A major exhibition devoted to Angelica Kauffman RA (1741-1807) closed last month at the Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf. The show’s long awaited second leg at the Royal Academy was sadly cancelled – as so many were this year – leaving London still longing for a worthy celebration of this exceptional artist. The Royal Academy exhibition would have been the first monographic show of Kauffman at the institution that she helped found in 1768. After a formative period in Italy, it was in London that she achieved recognition and fame, charming her sophisticated patrons and fellow artists alike. She would later return to Italy to set-up a successful studio in Rome.

Curated by the distinguished Kauffman expert Bettina Baumgärtel (responsible for the Angelika Kauffman Research Project), the Düsseldorf exhibition presented a selection of 110 amongst her finest works, both masterpieces and newly identified paintings, and succeeded in showing Kauffman as the first woman artist of European standing.

The four ceiling paintings Kauffman created for the Royal Academy’s Council Room in Somerset House travelled to Germany and were shown outside London for the first time since their unveiling in 1780. Unique in being major decorative paintings executed by a woman, they showcase Kauffman’s skills in inventing graceful yet commanding female allegories, through a persuasive blend of tradition and innovation. All four allegorical figures are, obviously, female. Notably, by depicting Disegno, traditionally a male figure, as a woman artist studying an antique model (the Belvedere Torso) Kauffman made a strong claim for the professional ambitions of women artists such as herself and her peers (Fig. 1). The exhibition also shed light on Kauffman’s working practice, visitors were able, for instance, to see the four large ceiling paintings showing Invention, Composition, Design and Colouring alongside the corresponding preparatory oil sketches, now held at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Born in Chur, Switzerland, Kauffman trained as both a painter and a musician, showing early promise in both disciplines. After the death of her mother in 1757, however, she devoted herself to painting – her father’s trade. In her Self-portrait at the Crossroads between the Arts of Music and Painting (1794) made in Rome, when she was in her 50s, she revisited the arduous choice she had faced as a young woman [1]. A blend of portraiture and history painting, this is the ultimate manifesto of Kauffman’s art: she gained success as a portraitist but aspired to the accolades that only history painting could bring.

The theme of rivalry between the Arts is also at the heart of an earlier autobiographical work, the Self-Portrait in the Character of Design Listening to the Inspiration of Poetry (Fig. 2) [2]. Here she upholds the value of sisterhood between painting and poetry: it is by following the guidance of Poetry that Design is able to give life to compelling and virtuous inventions, gaining her place amongst the liberal arts.

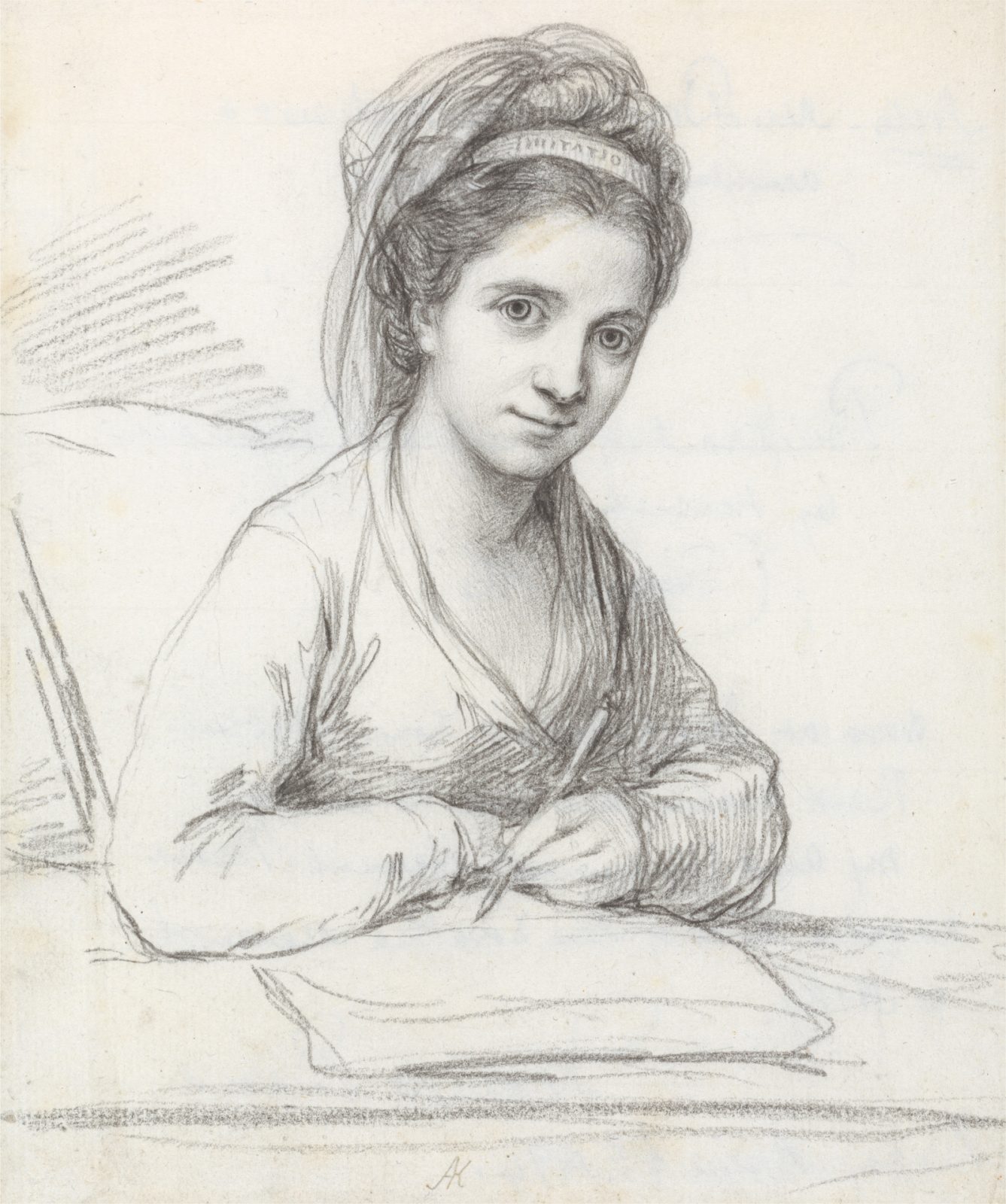

First developed by Horace in the Ars Poetica, the concept of Poetry and Painting as sister arts united by the power of imitation was expanded upon by Sir Joshua Reynolds in his Seven Discourses on Art, which in turn had a crucial impact on Kauffman’s own understanding of the kinship between the visual and liberal arts. Several drawings by Kauffman also relate to this theme. A well-known example is her Self-Portrait as Imitatio (Fig. 3), where a young woman, identified on her headband as ‘Imitatio’, sits at her desk holding a stylus, and looks out at us, as if interrupted while writing or sketching.

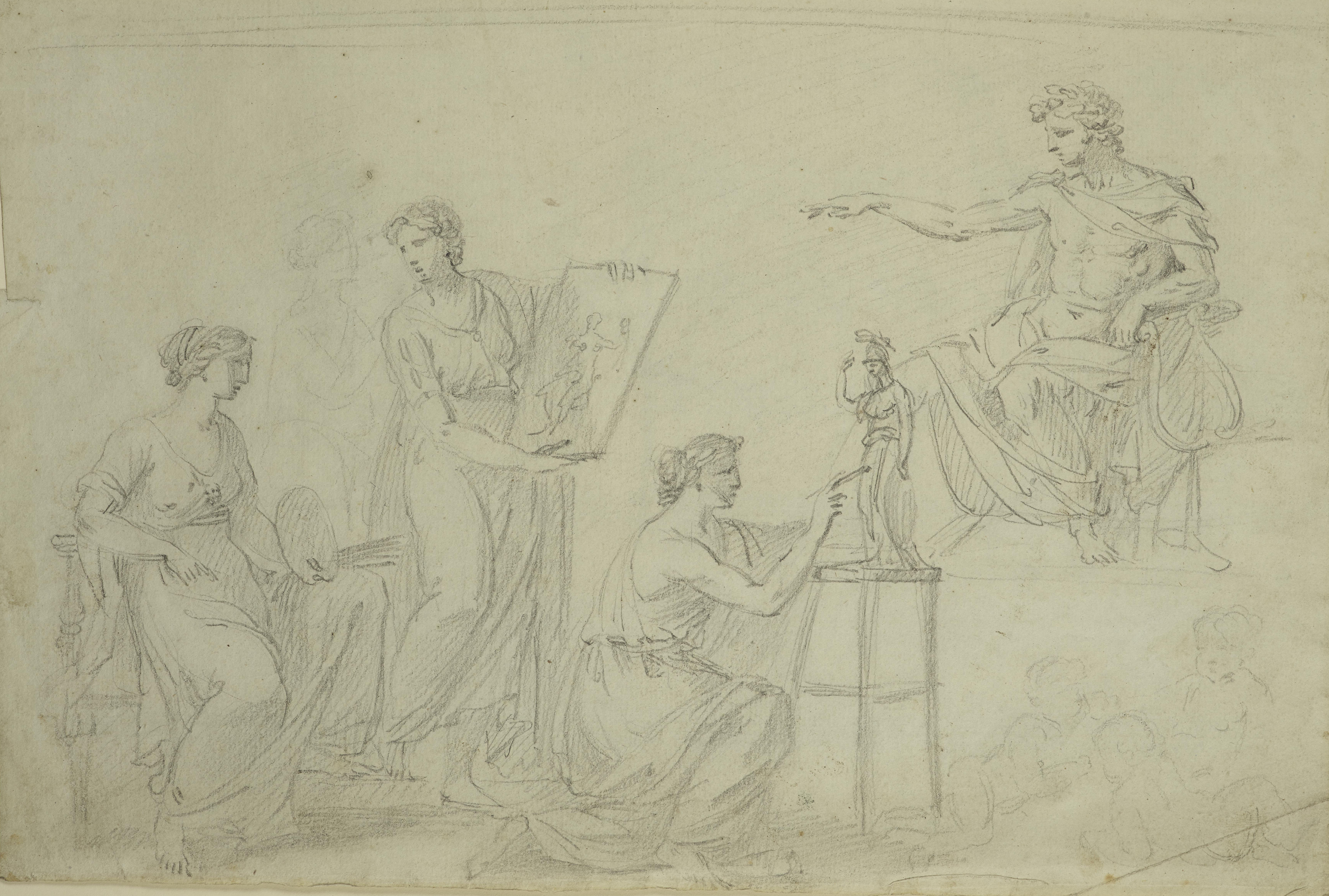

Kauffman’s composition known as The Three Fine Arts (Painting, Architecture and Sculpture) was disseminated in stipple engravings by Francesco Bartolozzi and Daniel Berger (Fig. 4), a channel through which many of her images reached a wider public. A drawing in the Katrin Bellinger Collection (Fig. 5), probably not by Kauffman’s hand, takes its lead from the same invention to draft what appears to be a more elaborate allegory. Here, Architecture has been replaced by Design. The faintly delineated figure standing beside her rests her right hand on Design’s shoulder, in a gesture reminiscent of the aforementioned Self-Portrait in the Character of Design Listening to the Inspiration of Poetry.

Kauffman’s works were reproduced, copied and even adapted for the decoration of porcelain and fans. Her success was such that, in 1781, the Danish ambassador in London quoted an engraver as saying ‘the whole world is Angelicamad’.

To learn more about the Angelika Kauffman Research Project visit: www.angelika-kauffmann.de/en/akrp-home-2/ (accessed 21 October 2020)

Explore related theme: Women artists, Allegories of the arts

Notes

[1] National Trust, Nostell Priory, Yorkshire; Bettina Baumgärtel, ed., Angelica Kauffman, Munich, 2020, cat. 2.

[2] Baumgärtel, ed., Angelica Kauffman, cat. 7

Fig. 1 Angelica Kauffman, Design, 1778-80, oil on canvas, 130 x 150.2 cm, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Fig. 2 Angelica Kauffman, Self-Portrait in the Character of Design Listening to the Inspiration of Poetry, 1782, oil on canvas, diam. 61 cm, English Heritage, The Iveagh Bequest (Kenwood, London)

Fig. 3 Angelica Kauffman, Self-Portrait as Imitatio, graphite, 200 × 168 mm, Yale Centre for British Art, inv. no. B1977.14.5552

Fig. 4 Daniel Berger after Angelica Kauffman, The Three Fine Arts, 1786, stipple engraving, 172 x 224 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 2019-05

Fig. 5 Circle of Angelica Kauffman, Allegory of the Arts with Apollo, pencil, 227 x 333 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. no. 1996-002

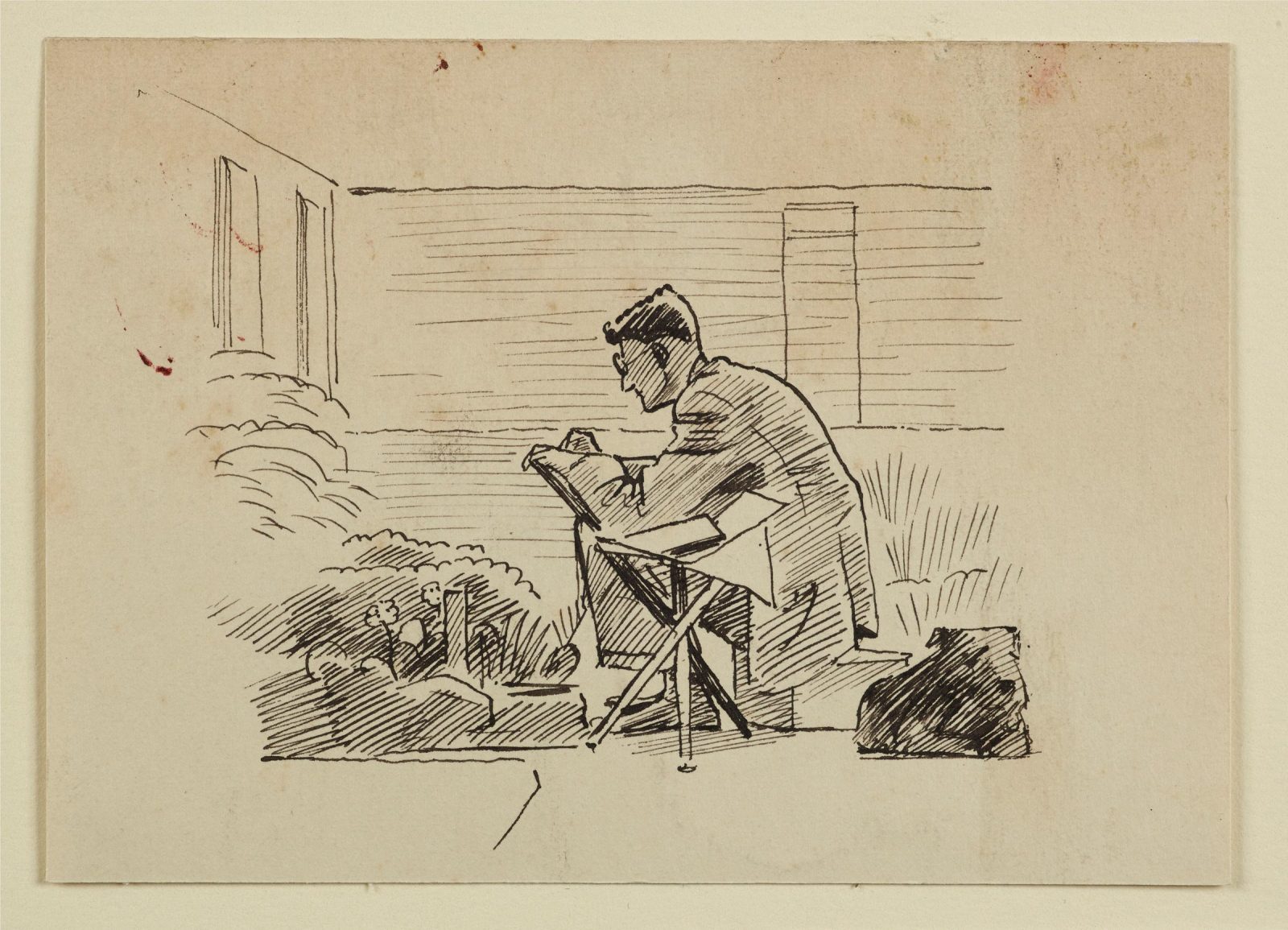

The Artist in Nature

The months spent staying indoors and working from home have made many of us long for the outdoors and a closer contact with nature, be it in our own back garden, the nearest park, or in the green spaces of our imagination. As the proliferation of exhibitions and cultural initiatives devoted to nature, botanical art and the pleasure of gardening attests, never before has the importance of preserving and enjoying nature felt more pressing than in the current global climate (just last week, I attended a webinar devoted to the practice of drawing weeds, learning more on the art history of weeds while also trying my hand at some observational drawing!) It will thus come as no surprise that I have turned to a group of depictions of artists working outside in search of some respite. As a disparate group, the four drawings briefly discussed here, exemplify the multi-faceted nature of the relationship between draughtsman and landscape and the enduring appeal of the motif of the artist at work out of doors.